On The Road: The Iconic Image: The Same, Only Different

Early on I lived in Paris, shooting fashion photography. I saw all the iconic places and landmarks, of course, and observed hundreds of people shooting them. When I became a travel photographer, my initial thought was to shoot lots of subjects other than the icons; to make untypical, evocative images of marketplaces, shop fronts, and unexpected details. Pretty quickly I found out the icons defined a place, and even more important, the icons made the money.

All Photos © Blaine Harrington

Today I do well with the iconic shots that I’ve placed with major stock sites, even though there are thousands of shots from other photographers of the same attractions. Somehow, my images are different, or different enough, to rate attention and sales.

Some of that difference has to do with technique, like capturing the saturated colors of sunrise and sunset, and sometimes boosting them in post-processing. And some has to do with equipment, like an extreme wide-angle or a long telephoto. But mainly it has to do with learning as much as I can about people and places; knowing what I want in a picture; and previsualizing the results.

A professor once told me that everything you know applies to everything you do. Sure enough, I’ve found the more I learn, the more I can do. Ultimately how you view the world and your awareness of your subject is just as important as the lens, the time of day, or the intensity of the colors.

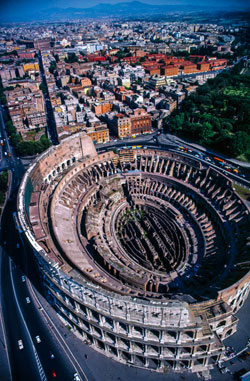

To take travel photographs that are different, that are more than the record shot of a place, that are a far cry from just jumping off the bus and taking pictures, you have to have a fascination for what you’ll be seeing. You have to know the history and the significance of the places and the sites, and how they fit into the lives of the people who live with and near them.

You’ll notice that there are people in many of my pictures, and often they are the major part of the image. People bring a sense of scale, but they also portray the landmark or world wonder in human-interest terms. People visit these places and they also live nearby and often see these icons peripherally as they pass by. Life is going on around the monument; the landmark is also a backdrop. Capture that element and your picture is going to be different from yet another “here’s what the Eiffel Tower looks like” shot. In other words, don’t isolate landmarks; rather, integrate them into people’s lives and create a human-interest aspect to the story.

Part of what I do involves previsualization and planning. I know I get better results when I put thought into what I want from the place I’m visiting. To get a different view, I’ve got to know what the different view is. I can’t be waiting around thinking that a different view will happen. If I know what I want to see, and then choose the lens, set up the flash, decide on the composition and the exposure, I’ll be more than ready when the elements come together. And when people are involved, it’s just practical to do it that way. If people are aware of me or if I need their cooperation, I find that they’ll have about 30 seconds worth of patience. If I want to get the image before the moment moves on, I’ve got to work quickly, smoothly, and confidently.

What I do to get different-looking images of familiar places and landmarks is first know their significance; second, know what I want the photo to look like; third, prepare all the technical and mechanical aspects so I’ll be ready when the picture is ready to be made.

I know what you’re thinking: what about luck? What about serendipity? You’ve heard that luck favors the prepared? Well, what the prepared are prepared for is luck. I believe that if I’m ready for luck, it will come my way.

A selection of Blaine Harrington’s travel photographs can be viewed at his website, www.blaineharrington.com.