Easy Infrared; Create Your Own From Any Color Image File

You can start with a scan of any color slide, print, or negative you've shot with your film camera or, even easier, with a color file from your digital camera. If you're starting with a print, negative, or slide, scan it in RGB color mode. Once you've got the digital file, open it in Adobe Photoshop CS (or some earlier versions) to follow the steps outlined here. You can also achieve the effect with Adobe Elements 2 or other advanced image-editing programs, but the names of some tools or dialog boxes may be slightly different. Always work on a copy to preserve your original scan. In fact, with this technique, it is a good idea to make two or three copies in order to try different settings in search of the effect you like best. Just follow these steps and you'll be on your way to easy IR.

|

|

|

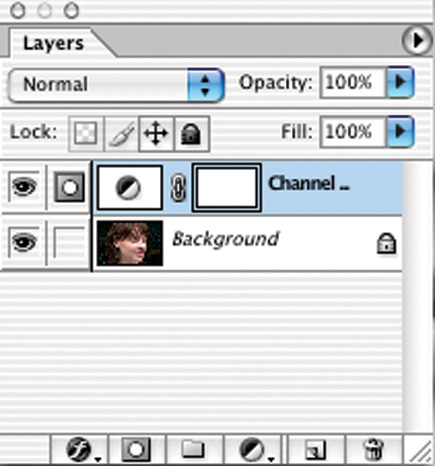

1) Open a copy of your color file in Photoshop #1. First, we'll convert it to black and white. By doing this with an Adjustment Layer, we never change the original pixels and can go back and make further changes as desired at any time. To add an Adjustment Layer, from the menu bar choose Layer>New Adjustment Layer>Channel Mixer, #2. A dialog box appears naming the new layer Channel Mixer 1. Click OK and you'll bring up the Channel Mixer dialog box, #3. This is a powerful tool to make black and white conversions (among other uses).

|

|

|

First, check the Monochrome box at the lower left of the Channel Mixer. This will change the Output Channel at the top to "Gray" ("Black" in Photoshop 5), indicating that you are outputting a gray scale black and white image. The Channel Mixer allows you to decide which amounts of the red, green, and blue channels will be used to create a black and white image. Begin with a high setting for red. Don't worry if your screen goes totally white or black during these operations--as you move the other sliders, you'll regain more normal tonalities.

|

|

|

Try setting the red all the way

to +200, then take the blue down to --60 or --75. The green middle

slider might go from --40 to +30, all depending on the image. Experiment

with many different mixes, and try the sliders throughout their full range.

However, you'll probably want to keep the red at least +100 to +120 minimum.

2) For this portrait, I set the red to +200, the green to --38,

and the blue to --60, #4. For a different portrait, +120 red, +32 green,

and --75 blue worked best. As you make the adjustments, you'll begin

to see the IR effect: In theory, you should adjust the percentages so that their

total equals 100 percent. This is not a hard and fast rule, though, and I often

find settings outside this range work well. The Constant slider near the bottom

of the Channel Mixer dialog box changes brightness. While I usually prefer to

leave it at 0, you may find it useful when the final mix of percentages is more

or less than 100 percent.

|

|

|

Here's a tip:

If you have adjusted the sliders for a look you like, but the image is a bit

dull or low in contrast, try adding a Levels or Curves Adjustment Layer, then

using it to pump up the contrast.

3) Images made with Kodak High Speed IR film often have an

eerie glow, partially caused by film halation. Now it's time to add that

IR glow effect to this portrait. Flatten the file by choosing Layer>Flatten

Image. Next, blur the image with Filter>Blur>Gaussian Blur, #5. The radius

amount will vary with the size of your file, so experiment. As a starting point,

try 5-20 pixels for a 25MB size image and 2-10 pixels for a 5MB image. In this

example, which is an 18MB size file, I found that a Gaussian Blur radius setting

of 5 worked well. Your screen image will now become totally blurred, but don't

worry.

|

|

|

Choose Edit>Fade Gaussian Blur, #6 (Filter>Fade in Photoshop 5). Click the Preview box and change the Mode of the blurred channel to Screen or Overlay. This is the blend mode which controls how each layer will interact or blend with the layers below it. Since the default blend mode is Normal, this is what you should first see in the Mode window in the Fade dialog box. Click on the double arrows and then select "Screen" or another mode from the Mode pop-up menu. You'll probably want to re-adjust the Opacity slider according to the mode setting you've chosen. Try Screen first, then Overlay. Sometimes, Overlay provides better contrast and richer blacks, but may make the image too dark. Again, you have to experiment. Try other mode settings, too, like Hard Light or Soft Light.

|

|

|

While you're still in the

Fade dialog box, drag the Opacity slider to the left to reduce the effect of

the blur. The amount varies with each image and with the amount of blur you

applied originally, so try a number of different settings. In some images, 5-25

percent works well, in others, 80 percent. In the example shown here, I found

that a fade to 30 percent worked well with the Screen blend mode, #7. But I

also liked the look with it cranked up to 60 percent, although a lot of detail

was blown out at this higher setting. Again, you can fine-tune the tonalities

and contrast with a Curves or Levels Adjustment Layer.

(Remember at the outset I suggested that you make several copies of your original.

Now is when you might want to haul some of those out and repeat the earlier

steps trying totally different Gaussian Blur, Mode, and Opacity settings.)

|

|

|

4) IR film exhibits

pronounced, gritty grain, all part of the IR aesthetic. If you want to add a

grain effect to your digital IR image, make a duplicate of your Background Layer

by choosing Layer>Duplicate Layer. Now, with the Duplicate Layer active (highlighted

in the Layers palette), choose Filter>Noise>Add Noise. The Distribution-Gaussian

setting usually works best while the Amount varies according to the size of

your image. Play with the slider until you see the look you like. Be sure to

check the Monochromatic box at the bottom. When this is on, noise is applied

the same to all color channels. When off, the effect is random for each channel

and can introduce unwanted color in your monochromatic image. As with the Gaussian

Blur, you can experiment with different blend modes for this grain layer. Try

Edit>Fade Noise and try different blend modes such as Multiply and Darken.

If the image with added grain is too low in contrast or too dark, flatten the

image and apply Levels or Curves to adjust the tonality and contrast if you're

working with Elements 2. With Photoshop CS, add a Curves or Levels Adjustment

Layer and group it with the background copy. Then in CS, to compare the last

IR effect to the one with grain, simply go to the Layers palette and click the

eye icon for the noise (grain) layer on and off. You may prefer not to add grain

for some subjects. I tried it with this example and decided that I preferred

the smooth sculptural skin tone without grain.

5) Yet another filter to experiment with that enhances the

IR effect is Filter>Distort>Diffuse Glow. You can try it instead of Gaussian

Blur as described earlier. Or add it after you've applied a Gaussian Blur.

Finally, for the richest results from a desktop ink jet printer, keep your file

in the RGB color mode and print in your printer's color mode. Your print

will still be black and white, but you'll be using all the inks instead

of just black for a smoother, deeper print. For striking black and white portraits

such as this, I prefer to print on a heavy art paper such as Luminos Classic

Velour. A matte or slightly textured paper enhances the fine art feel of IR

imagery.

These operations take much longer to describe than to actually perform. So open

up one of your favorite color portraits and take it in to the eerie and dramatic

world of IR.

Contact

Adobe Systems Inc.

(800) 833-6687

www.adobe.com

- Log in or register to post comments