Portrait Art: Art Wolfe Captures The Human Canvas

To say that Art Wolfe is not your typical portrait photographer is quite the understatement. With a career spanning 40 years, Wolfe brings his travels from every corner of the earth to create stunning portraits in his Human Canvas collection, honoring the traditions of Ethiopian tribal culture.

The son of commercial artists, Wolfe majored in fine arts at the University of Washington. He believes his training in the arts has a “100 percent influence” on his work. The Human Canvas draws from a variety of Wolfe’s books on camouflage and tribes that celebrate creativity in remote villages. Other influences include Keith Haring’s work as well as Indonesian batiks. “With my training in art I definitely have the ability to pick up a brush with confidence,” he says. “The Human Canvas is far less about photography than a conceptual idea of a ‘creation.’”

Wolfe is mainly known as a nature photographer, but has always photographed people as well. His first camera was a Brownie Fiesta that as a child he thought was pure gold. After high school he became an avid mountain climber, and using his father’s old Speed Graphics he started shooting 4x5 black and whites on the tops of mountains. He didn’t know about a lot of galleries, but was able to convince local outdoor gear stores such as REI, Eddie Bauer, and The North Face to hang his photos on their walls. He later joined fellow hikers in the Boeing camera club (even though he never worked there), but otherwise learned photography by trial and error. Wolfe soon realized that photography suited his temperament more than painting, as he loved the immediacy of it to create compositions rather than making drawings from his imagination. He was fortunate to have a friend who was dating an assistant to a managing editor at National Geographic, and she made a call for him in the late 1970s. “In those days the editors liked photographers with confidence and ‘chutzpah,’ so four years after graduating from college I got my first assignment from them.”

In 1978 Wolfe published his first book, Indian Baskets of the Northwest Coast, with the late Dr. Allan Lobb, a close friend and mentor. In addition to National Geographic, Wolfe was soon photographing for the world’s top magazines, including Smithsonian, Audubon, GEO, and Terre Sauvage.

Bringing Ethiopia To Seattle

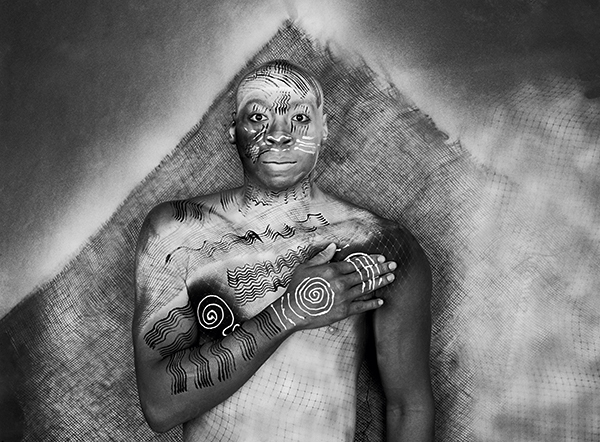

For the Human Canvas project, Wolfe drew heavily from the images he did for his book Vanishing Act, a collection showing how evolutionary traits benefit animals in disguising themselves from predators. He chose to study the tribal communities of southwest Ethiopia, where he had first visited 25 years ago, in one of the few areas that had never been exploited for mineral resources. “The five distinct tribes there remain very traditional, with many wearing only a single piece of robe over their shoulder. The temperature is comfortable but the sun is relentless,” Wolfe says. “To protect their skin from the sun, they cover their bodies with clay made from the waters of the nearby Omo River. Eventually that developed into design.”

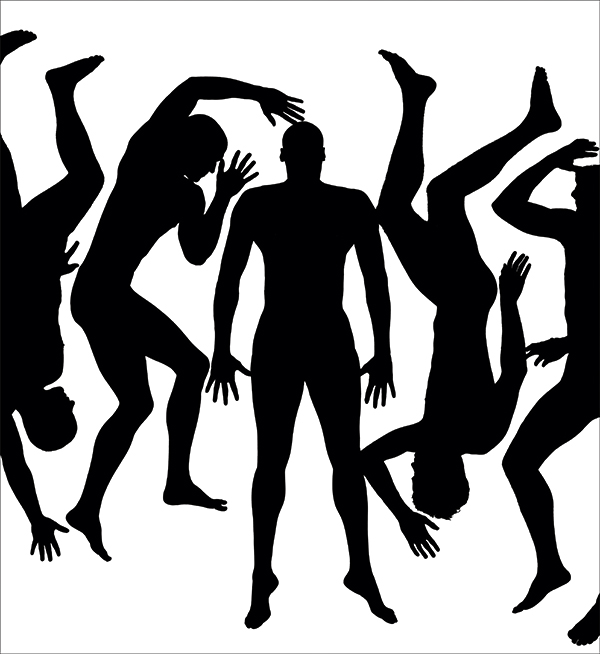

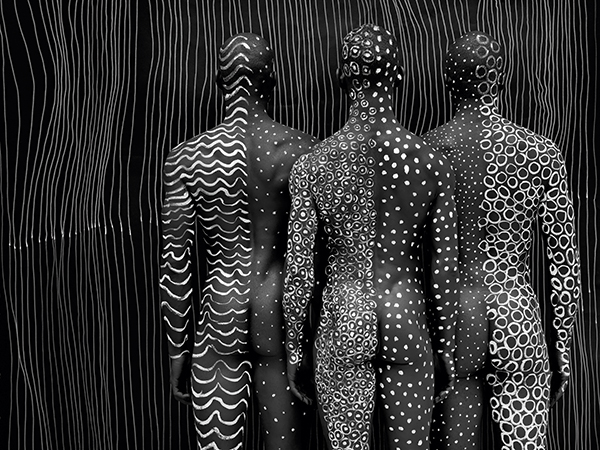

Wolfe decided to recreate the ornamental decoration of spots, lines, and textures that remote peoples use during ceremonial occasions back home in a studio in Seattle. There he could control the lighting and use his own talents as a painter to emulate the beautiful designs and cover bodies with clay. He advertised for volunteers at local gyms, and was amazed to get over 100 responses from doctors, athletes, professional trainers, and dress designers. “There were no professional models, and everyone had goodwill and good energy that enabled me to concentrate on the work,” Wolfe recalls.

“I tried all different elements to create a new dialogue for the human form. I wanted to celebrate it and explore the idea without being sexually suggestive or even sensuous. It’s much more theatrical, and my intent also was to connect humans with the earth through the use of clay and a nod toward tribal art. Using the concept of camouflage, I would paint really ornate backdrops, spray paint people either solid white or black, and then paint them like the backdrop until you could almost not tell they were in front of you.”

With a plan to display the collection in museums and art galleries, Wolfe used an 80-megapixel Phase One medium format camera as well as a Leica. “I want to see the photos displayed life size on museum walls, and hope to showcase the collection along with a new project again next year that will include animal skulls and other forms.”

Documenting Ancient Cultures

In addition to the love of travel and photographing people, animals, and landscapes, one of Wolfe’s main goals during the last 30 years has been to document the rapidly disappearing cultures of remote traditional peoples. “After I came back from Tibet in the winter of 1984, I resolved to travel as far abroad as I could. I’ve made multiple trips to the Amazon, the Outback of Australia, the hill tribes of Southeast Asia, and the deserts of Africa. Many of the photos I took in these places could not be replaced now. Western civilization has even invaded the mountains of New Guinea, for example, where people are wearing American baseball caps the last time I was there. So the culture looks like it has been tampered with in my estimation.”

In 1993, Wolfe was approached by a production company to be the host of “American Photo’s Safari,” which aired on ESPN. He would take celebrities out to teach them photography on location, and had the ability to “look in the camera while not falling down. I realized years later that the goal of all my books was to inspire, educate, and uplift people. If a TV show was successful it would reach a much larger audience than a book.” In response to the 9/11 attacks he had his own public television show with the high-definition series “Art Wolfe’s Travels to the Edge.” He says, “I wanted to show there was a big world out there and we can’t be held captive to our fears.”

Photography As Business

“Success comes from photographing seven days a week,” Wolfe says. He works with seven other professionals and believes that part of his success is due to his ability to let go of certain aspects of projects. For example, he’ll let others take care of post-processing and final tweaking of an image that other photographers might want to do themselves. He is also very active on social media, producing blogs and an e-zine. “To be successful you have to reach audiences, so social media is something you’d better do or you will be out of business.”

Today he frequently conducts photography tours and offers “Art Wolfe’s Art of Composition Seminars” for photographers of all skill levels to learn photography composition and techniques. Wolfe’s next workshop will be in Antarctica. He is planning two new books, one on austere landscapes around the planet and the other that looks at the world’s religions, which should be very timely. “I once worked with an editor at Random House who was 95. Before we would finish one book he always had an idea for the next one. I think he was using me to keep alive. In the same way, I think my background in painting and art taught me to always be thinking and creating, and that has served me well over the years.”

For those interested in a career in portrait photography, Wolfe suggests first studying the work of others. “Look at Irving Penn’s portraits or Anne Geddes’s to educate yourself as to what other people are doing. See what you like about it and try to replicate it to at least get the start, and hopefully you will morph into your own person.”

Art Wolfe has published over 80 books, including Vanishing Act, The High Himalaya, Water: Worlds Between Heaven & Earth, Tribes, Rainforests of the World, The Art of Photographing Nature, and The Human Canvas. He has received numerous honors, including Nature’s Best Photographer of the Year Award, the North American Nature Photography Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the Photographic Society of America’s Progress Medal, the Alfred Eisenstaedt Magazine Photography Award, and a first-ever Rachel Carson Award given by the National Audubon Society. Additional photos from the Human Canvas collection can be viewed on his website, artwolfe.com.