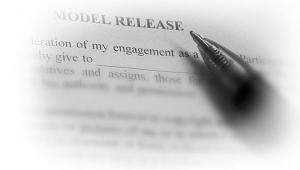

Model Releases: Fact & Fiction, And Some Case Studies

As I did my research on model releases it became clear that this is not a black-and-white issue. The law and the practice of the law seem divided. The aim here, then, is to present you with a point of view that is both practical and supported by industry custom. First, let’s try to separate this discussion from copyright. Copyright law is the federal protection of your right as the owner of the work you created to control the use of that image. You create it, you own it. Rights of privacy and publicity laws protect the individual’s rights to control the commercial use of their likeness and they vary from state to state. There are exceptions to this: the use in news media of a person’s likeness is not considered commercial and does not require their permission.

Second, the most hotly debated topic is whether you need model releases to use your images of recognizable individuals in your self-promotion pieces. Since business sense dictates that your self-promotion is not editorial, most photographers take the safer legal position that marketing your photography is a commercial use and you should get model releases.

The bottom line is that getting model releases increases the sales potential of any image for the commercial use in stock photography. Let’s see what the professionals we interviewed have to say.

A M Johnson (http://cafe1956.com) reviews the “letter of the law” on the federal and state levels: “The value in securing a model release is in the usage a photographer gets out of it. As the creator of an image or original work, the photographer has an ironclad copyright the moment the shutter release is pressed. The image is theirs and theirs alone at this point. The model has no right to the image in any way. Because of state laws governing usage, the photographer only has limited rights to use the image, even though he or she owns it. This is the fundamental difference between copyright and usage. Just because you exclusively own the photo, you may or may not be able to use the photo. Federal law allows ownership, state law allows usage. This is typically called the right to privacy or the right to publicity.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ben Lawson (www.benlawsonphotography.com) describes a case where he wished he had asked for a model release: “I had a model a couple of years ago who gave me a lot of headaches when she came back and demanded high-resolution ‘raw’ images of everything we shot together. I had neglected to get a model release, so I removed her images from my portfolio because I would not give in to her demands. This was not a test shoot; this model contacted me through a popular modeling site. At the time, I did not have information posted regarding what models would receive and what to expect from a shoot (I do now). I was aware of the use of model releases, but at the time all of my work was strictly personal and not being used for advertising or commercial purposes at all, which—right or wrong—made me more relaxed in my model release policy. Considering this model’s angry reactions, my wife and I were concerned about my reputation. I then sent the model a letter explaining again what her legal rights were in regard to the images, and asked her then to sign a model release which I enclosed. I told her that I had the right to have my images removed from her modeling portfolio if she refused, but that I didn’t want to have to do that. It took a few weeks, but she eventually signed and returned the release. Since then, I have been more diligent on getting model releases, especially with models I’ve never worked with.”