Mary Ellen Mark: Looking Back on the Career of a Pioneering Photojournalist

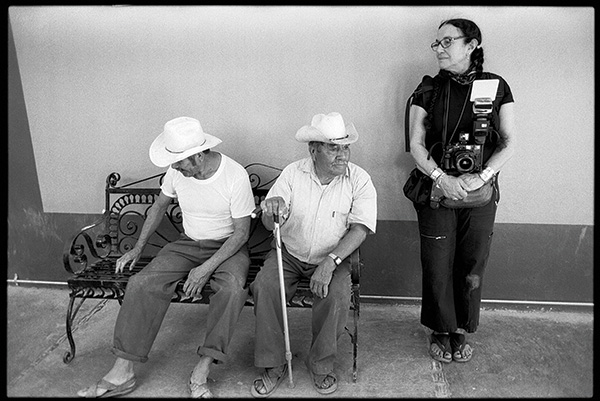

This interview with Mary Ellen Mark took place before her death on May 25, 2015, at the age of 75. Considered to be the ultimate “humanist” photographer, she will always be remembered for the honesty, compassion, and empathy she gave to everyone.

Is a photograph that is completely changed using Photoshop “real”? Mary Ellen Mark never thought so. After 50 years of achievement in documentary photography, Mark preferred “photographing reality and real people.” Whether it was living and working among the mentally ill or in a home for the dying in the slums of Calcutta, Mark’s photos are breathtaking because she earned the trust of her subjects.

As a child Mark was always looking through family photo albums, and enjoyed taking pictures of friends at school and summer camp with her Brownie camera. (Some of these later appeared in the 1971 film Carnal Knowledge as part of a slide show shown by the character played by Jack Nicholson.) Always good at painting and drawing, she majored in art at the University of Pennsylvania thinking she might want to be an architect or a painter, but “painting was too isolating.” After being awarded a scholarship to the university’s Annenberg School for Communications, she picked up a Retina camera for an assignment and “knew photography was exactly what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

Mark had always planned to travel and experience other cultures, and was fortunate to receive a Fulbright scholarship to photograph in Turkey. She spent two years traveling throughout Europe and then returned to New York City in 1967 to take pictures of street life in Central Park and Times Square. Her subjects usually included those living on the fringes of society such as transvestites, pro- and anti-war demonstrators, and those promoting the women’s movement. “I’m always interested in people on the edges. I feel an affinity for people who haven’t had the best breaks in society.” Throughout her long career, this proved to be quite the understatement.

© Mary Ellen Mark

Movie Stills Lead To Documentaries

A friend was working at MGM Studios in Hollywood, and she showed a director Mark’s portfolio. Mark was immediately hired to take photo stills for the movie Alice’s Restaurant and that lead to other assignments.

Considering this work commercial, Mark said, “The most important thing for me is to do my personal work. You have to have your own point of view and your own pictures.” She asked director Milos Forman if she could work on his new movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest to be shot on location at Oregon State Mental Hospital. Perhaps in part because her father had been placed in a mental hospital several times, “I’ve just always been interested in mental health and mental illness.” (Mark believed that “everything from your childhood has an influence on who you are as a person.”) While shooting photographs for the movie, Mark got to know the hospital’s director who introduced her to the women in the maximum-security ward.

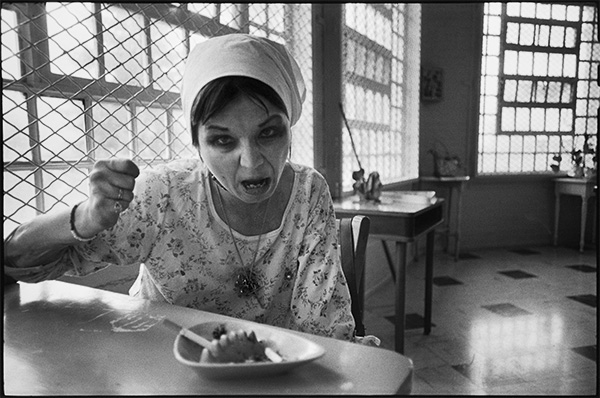

This was the beginning of Mark’s ability to live among those she was photographing for an in-depth series on people’s everyday lives. She returned to the hospital with writer Karen Folger Jacobs and lived for a month with the patients of Ward 81. She earned their trust because she wasn’t an authority figure like the nurses and doctors who could hand out punishments. As the patients got used to her being around Mark was able to capture their individual personalities in a very stark environment. As just one example from her book Ward 81, in Mona we can immediately feel the hopelessness and sadness of a patient’s life there.

© Mary Ellen Mark

Among The Prostitutes Of Falkland Road

Mark loved to work with black-and-white film “because it takes you right down to the basics. The most important thing in a photograph is the content, not the decoration.” But the editors of the magazines Geo and Stern requested she use color for the Falkland Road series on prostitutes in Bombay, India.

Mark had tried several times in previous years to photograph the residents there, but had encountered a lot of resistance. This time she befriended a few street prostitutes who didn’t work for a madam as well as a group of transvestites who enjoyed being photographed. Eventually two madams asked her to stay with them for weeks at a time and even hid her under a bed during a police raid.

“I’m glad I did the Falkland Road pictures in color since color was such an important part of their lives,” Mark recalled. She playfully named her photography business Falkland Road Inc., upon the advice of a regular customer who said she should bring back some girls from New York City and open her own brothel there.

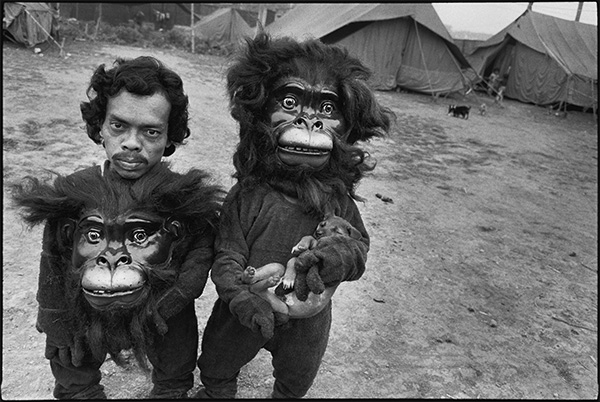

Traveling Circuses Of India

In another long-term project, Mark photographed members of 18 different circuses in India, including child contortionists, acrobats, dwarf clowns, and the trained animals. In the preface to her book Indian Circus she writes, “Photographing the Indian circus was one of the most beautiful, joyous, and special times of my career. I was allowed to document a magic fantasy that was, at the same time, all so real. It was full of ironies, often humorous and sometimes sad, beautiful and ugly, loving and at times cruel, but always human. The Indian circus is a metaphor for everything that has always fascinated me visually.”

© Mary Ellen Mark

Streetwise

Perhaps Mark’s best-known photo is a skinny teenager in a little black dress with arms crossed and a defiant and angry look on her face. Known as Tiny, she was a 13-year-old prostitute and drug addict on the streets of Seattle. Dressed for Halloween to “look like a French whore,” others say she looks dressed for her own funeral.

Mark met Tiny while on another assignment from Life magazine for a photo series on street kids in Seattle in 1983. This started a 30-year relationship and Mark has photographed just about every aspect of Tiny’s troubled life. Today Tiny has gained a lot of weight and had 10 children by five different men, but is happily married, quit drugs, and lives as a suburban housewife.

The Streetwise series also lead to the first joint project with her husband, filmmaker Martin Bell. After telling him about a kid who roller skates down the hallway of an abandoned building, he agreed it would make a great film. Knowing all the street kids and their relationships, Mark worked as a go-between and could plan out who might be where and when. The film ended up being nominated for an Oscar award.

For the series on the Damm family, also commissioned by Life, Mark spent two weeks with them as they lived out of their car with their two children and a dog. As Mark wrote in her book Exposure, “I learned how important it is to stay with a subject and become part of his or her daily life. I also learned you can capture more intimate moments by blending into the background.”

© Mary Ellen Mark

A Devotee Of Film

Mark was reluctant to switch to digital as she loved “the negative and silver prints, and it’s difficult to make a transition. My pictures have a certain look and a certain style and I think it’s important to stay with that.”

She worked with a variety of cameras, including a Leica 4 “my first serious camera,” Nikons for long-range shots, a Mamiya 7 and a Hasselblad for square format. For her more recent books, Prom and Twins, she rented a Polaroid 20x24 that she loved. “With that camera and film, the photograph becomes an object, something more.”

In recent years, Mark bemoaned the lack of documentary photography, saying that news outlets are only interested in disasters and war, “which is a very dangerous thing to cover. We don’t see a documentary project that is personal and not connected with something in the news.” She most recently gave workshops in Mexico, New York City, and Iceland and while digital cameras were more than welcome, Photoshop could only be used as a darkroom. “When people are inserted into a group picture or heads are inserted, that’s not real.

“The reason why I love being a photographer is because I love the idea you capture a moment in time, a moment of reality in time. Whether it’s a portrait of an actor or somebody on the street, it’s a moment of reality. The whole talent and gift of being able to capture a moment has been forgotten.

“The people I grew up loving such as Henri Cartier-Bresson caught that decisive moment; were able to capture and stop a moment in time in such a brilliant way. A changed moment is really just an illustration.”

Mark’s parting words of advice were that “everyone should be their own person. It’s really important to have your own point of view. Separate between what’s assigned and what’s really yours.”

To view other photographs by Mary Ellen Mark, from the well known to the obscure, and for a list of her 18 books, visit her website: www.MaryEllenMark.com.