Buying A Lens; Tips On Making The Right Choices

In deciding which lenses to buy, there are various factors that come into play. I will discuss each of these factors, and then at the end of this section I will recommend which lenses I feel you should have when starting out in photography, and then I’ll give you a wish list for future purchases.

1. Cost: Lenses are expensive, and unlike computer hardware and software, their prices don’t go down over time. They usually go up. You know what your budget is, and this will be the most significant factor in making a decision. You get what you pay for, however, and as I discuss the various factors that are involved in choosing a lens, you will see that money is part of the consideration at every level.

2. Focal Length: The focal length of a lens is the distance from the front glass element to the point in the rear of the lens where the image is focused. This definition isn’t really important, though, in terms of buying a lens. What is much more important is what type of pictures you like to take. For example, if you shoot a lot of sports, wildlife, or birds, you will need a telephoto lens to magnify the subjects in the frame so your pictures have more impact. To take the close-up of a leopard (#1), I used a powerful telephoto lens and this made a huge difference in producing a successful picture. Had the cat appeared much smaller in the frame, it wouldn’t have been a strong photo. Similarly the frame-filling shot of an Abyssinian Roller (#2), is dynamic simply because I used a telephoto lens to take this close-up photograph.

All Photos © Jim Zuckerman, All Rights Reserved

Telephotos are defined as any lens with a focal length longer than 50mm. A 50mm lens is considered “normal” because it approximates what we see with our eyes. The longer the focal length of the lens, the more magnification you will have. If you want to fill the frame with the face of a friend who is posing 10 ft away, you can use a 200mm lens. If you want to fill a significant part of the frame with a small bird on a branch about 30 ft away, you would need a much longer telephoto like a 500mm or 600mm. As the focal length increases, so does the cost.

If you like to do landscape and/or architecture photography, you will want to get a wide angle lens. I recently spent 5 weeks shooting in Europe, for example, and most of my best shots of the classic European cathedrals, castles, and palaces were done with wide angle lenses.

Wide angle lenses are defined as having a focal length less than 50mm. As the focal length decreases—24mm, 16mm, 10mm, etc.—the angle of view increases. In other words, the lens is able to include more in the picture. Extreme wide angle lenses have unique perspectives, and they exaggerate the graphic design in a shot dramatically.

Study photos (#3, #4, and #5). This gives you a sense of what the various focal lengths will do for you. All of these were taken from the same shooting position, and I used a 24mm, 70mm, and 200mm focal length lens, respectively. This beautiful location is Lake Bled, Slovenia.

3. Zoom Lenses: A zoom lens is one that offers a range of focal lengths in one lens. Zoom lenses can be constrained to the wide angle part of the focal length range, such as a 16-35mm or 10-22mm; they can be only in the telephoto range, like a 70-200mm or 200-400mm; or they can include both wide angle and telephoto. Two examples are 24-105mm and 18-200mm.

The advantage of a zoom is obvious. It’s very convenient to have a range of focal lengths built into one lens. It’s easier to carry only one lens instead of two or three, and without changing lenses you can quickly compose a scene in different ways. This can prevent you from losing a great opportunity. The disadvantage is that sometimes they tend to be a little less sharp than fixed focal length lenses. This is especially true when the zoom range is large, like in a lens that’s 18-200mm. The other disadvantage is that they tend to have smaller maximum lens apertures compared to lenses that have a fixed focal length. (See the 4th point.)

Some zooms are designed so when you change focal length, you slide a collar back and forth on the lens. Other designs give you a rubber-knurled ring that rotates to change the focal length. In considering the purchase of a zoom, I would strongly suggest the latter design. It gives you more control and it’s easier to operate.

4. Maximum Lens Aperture: All lenses have an aperture built into them. This is the opening through which light enters the camera to record an image on the digital sensor. The aperture opens and closes, and, in conjunction with the speed of the shutter, this determines whether or not your pictures are properly exposed. The maximum aperture is critical for this very important reason: In low light situations like the twilight shot of Gdansk, Poland (#6), you need to gather sufficient light with a large aperture because this enables you to use a fast enough shutter speed to ensure sharp pictures. Assuming you are hand-holding the camera (as opposed to using a tripod), a minimum shutter speed of 1⁄60th of a second is required. The large aperture must accumulate enough light to permit that speed.

A “fast lens” is one with a large maximum aperture, such as f/2.8 or even f/1.4. The larger the lens aperture, the more it costs, the heavier it is, and the larger it is.

Here’s a real situation that happens all the time. You see bird in a tree on a cloudy day (#7), and the light level is very low in the deep shade. If your maximum lens aperture is f/5.6, the shutter speed could very well be as slow as 1⁄30th of a second if you are using a low ISO for maximum picture quality. Even with a tripod, this is too slow for this kind of subject, and the result may be a blurred picture. On the other hand, if your maximum aperture were f/2.8—two f/stops larger (f/5.6>f/4>f/2.8)—then you could use a shutter speed of 1⁄125 (1⁄30>1⁄60>1⁄125). That’s the kind of difference that can make or break a picture.

A large maximum aperture is worth its weight in gold. In countless situations, from dim cathedrals to active children playing outside on a cloudy day, large maximum apertures mean the difference between sharp pictures and images that are soft or significantly blurred. They can also mean the difference between being forced to use a tripod to get a sharp picture and being able to hand-hold the camera. Yes, you can always increase the ISO to get that faster shutter speed, but the downside to that is there is an unwanted increase in digital noise and a degradation to overall picture quality when you do so.

Two defining aspects define all lenses: focal length and maximum aperture. Lenses are defined, for example, as 400mm f/4.5, 14mm f/2.8, or 50mm f/1.4. This gives you the most important information about the lens that will help you decide whether or not you want to buy it.

With zoom lenses, you will often see a range of f/stops such as f/4.5-f/6.3. What this tells you is that at the widest focal length the maximum aperture is f/4.5, and when the lens is zoomed out to the longest focal length, the maximum aperture will be f/6.3. A 70-300mm lens, for example, would most likely be used at 300mm with animals and birds, and this is where the maximum aperture is the smallest—f/6.3 in this example.

Unfortunately, large f/stops (fast lenses with wide maximum apertures) increase the price of a lens significantly. Super telephoto lenses in the 400mm to 600mm range can cost literally thousands of dollars more when you opt for a maximum aperture of f/4 versus f/5.6. A single f/stop, though, can make a huge difference in sharpness when shooting in low light conditions.

5. Magnification Factors: Camera manufacturers make many of their camera bodies with less than full-frame sensors because this makes them more affordable. A smaller sensor means that when you make a large print, the quality of the image won’t be as good as what a full-frame sensor (which has a larger physical area and therefore more pixels) would give you. With the advancement in technology, though, smaller sensors will still give you strikingly beautiful results in very large prints.

The point I want to make is that because the sensors are smaller, they crop some of the picture area, (figure #1). A full frame sensor includes the entire area of a typical 35mm piece of film, but as you can see in the diagram the less than full-frame sensor crops into the photo. Canon’s crop is slightly more than Nikon’s. The way you can determine what your actual focal length is for each lens is to multiply by 1.5x for Nikon lenses and 1.6x for Canon. (Note: Some camera bodies, such as the 4⁄3rd System cameras, have a 2x factor. Check the camera companies websites for the multiplication factor of your camera sensor.) A 70-300mm Nikon zoom, for example, becomes a 105-450mm lens. A similar Canon lens would be 112-480mm. This works to your advantage when shooting sports or wildlife because it’s like having a longer lens with no additional cost. Of course, if you took a picture with a full frame and used Photoshop to magnify it 1.5 or 1.6 times, you’d get the same result.

On the wide angle end of the spectrum, the magnification factor works against you. A Canon 16-35mm wide angle zoom becomes a 25-56mm lens, and if you like extreme wide angle perspectives you’ll be disappointed. A 25mm focal length is a decent wide angle, but it’s not as dramatic as a 16mm.

To address this problem, both Canon and Nikon (as well as third party lens makers like Tokina, Sigma, and Tamron) have produced lenses like the 10-22mm and 12-24mm specifically for less than full-frame cameras. When you calculate the actual focal length of Canon’s 10-22mm ultra wide angle lens by multiplying 1.6, the real focal length is 16-35mm. With Nikon’s 12-24mm you are actually shooting with an 18-36mm lens.

6. Image Stabilization (Vibration Reduction): When you hand-hold a lens, it’s impossible to be perfectly still. The lens has a certain amount of movement, and with telephoto lenses the movement is magnified. It’s very easy to see why images can be blurred in these situations, especially when a relatively slow shutter speed is used.

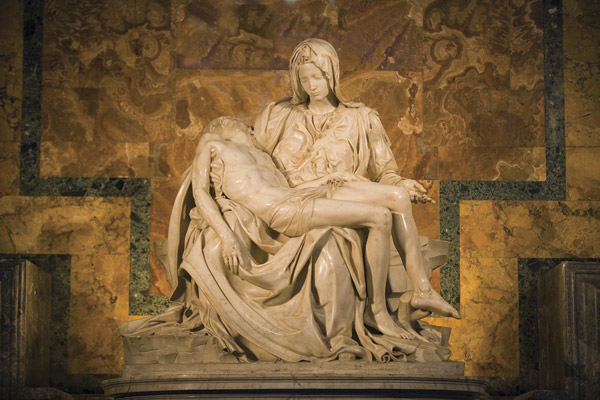

Lens manufacturers have built into some of their lenses—usually the telephotos or telephoto zooms—a feature that Canon calls Image Stabilization (IS) and Nikon calls Vibration Reduction (VR). Whatever the system is called, this mechanism counteracts the movement of the lens and permits sharp pictures even with shutter speeds like 1⁄30th of a second and sometimes slower. I experimented with IS when shooting my Canon 70-200mm lens in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. No tripods were allowed, so I had to hand-hold this heavy lens in the dimly lit cathedral. To be honest, I was shocked that pictures I took at 1⁄10th of a second were sharp. Keep in mind that the statues (#8) and architecture I was shooting weren’t moving, but this was still extremely impressive.

7. Sharpness: The one aspect that photographers always talk about with respect to a lens is its sharpness. Obviously, this is a big deal in photography. If you are a snapshooter and your primary interest is getting some nice shots of the grandkids, then whether or not a lens is tack sharp from the center to the corners isn’t a major concern and, to be honest, it won’t affect your enjoyment of taking pictures. If, however, you are exacting in your work and you will examine your images with a critical eye, then the quality of your lenses is very important.

Lenses are generally sharper when they have a fixed focal length. In other words, a 50mm lens will be sharper than a zoom that encompasses this focal length, such as 18-55mm. Depending on the individual lenses involved, this difference may be slight or it may be significant. In the past, zoom lenses were quite a bit softer than fixed focal length lenses, but now those differences are usually slight.

If a lens is less than tack sharp, this can be seen readily at the edges of the frame and particularly in the corners. If your primary interest in photography is portraits, this may not matter to you because subjects are normally placed in the center of the frame, which conveniently is the sharpest area of the lens. However, if you love doing landscapes, it can be very disappointing to have less than sharp corners. When you make a large print, the degradation in image quality will be obvious.

If you have the opportunity to test a lens before you buy it, take some pictures with it. Use a tripod as well as the mirror lockup feature and a cable release or self-timer. Shoot something stationary so there is no movement involved at all and use an f/8 aperture, which is the sharpest position for a lens (also test the lens with other apertures, too, so you can determine how sharp the lens is wide open and closed all the way down to the smallest aperture). Examine the images on your computer at 100 percent magnification. This will tell you what you need to know about the lens. You will not only see differences between manufacturers, you will see variations among the same lenses in one brand.

8. Chromatic Aberration: If you enlarge a photograph on your monitor to at least 100 percent, many times you will be able to see color fringing at the edges of the various elements in the composition. The fringing is usually magenta, cyan, and/or red, but other colors can sometimes be seen as well. An enlargement of (#9) shows this clearly. In (#10), look along the branches and twigs to see the colors that unfortunately occur. This is chromatic aberration. It happens more with wide angle lenses than with telephotos, and it appears more in the corner and edges of an image as opposed to the center.

Chromatic Aberration is the unwanted dispersion of light caused by the fact that colors of the white light spectrum (including the red, green, and blue that make up the channels or components of a digital image) are focused on slightly different places on the sensor. This is a function of how glass bends light. Lenses that have been corrected for this problem are said to be achromatic. Even with modern technology, however, this problem is never corrected completely. Lenses that are very expensive still capture images with color fringing in the corners.

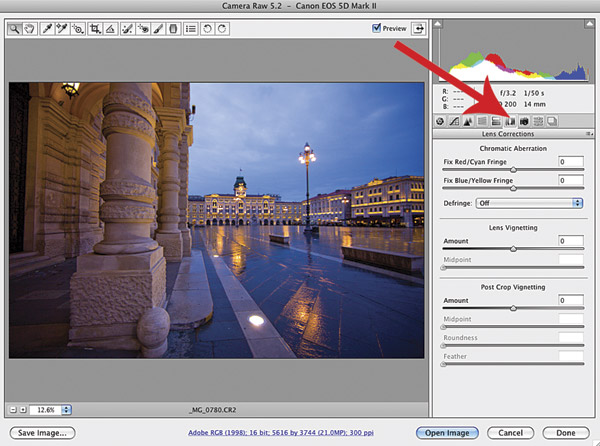

The best solution to this problem is to shoot in Raw mode and then use a Raw image processor, like Adobe Camera Raw (or Lightroom) to eliminate the fringing. The red arrow in figure #2 shows the icon in ACR that gives you the menu where this takes places. The top two slider bars just under the heading “Chromatic Aberration” allow you to miraculously get rid of the unattractive color fringing.

Recommended Lenses For Beginners

If you are a beginner in photography and want to minimize your initial investment, a good zoom lens would be ideal. For a full frame sensor camera where the magnification factor doesn’t come into play, I recommend a 24-105mm lens. This is a great range, and you can do landscape work, architecture, family, portraits, and flowers and be very happy with the results.

If you have a camera like a Canon Rebel, Canon 50D, or Nikon D300 that have less than full-frame sensors, then you could get a lens like the Sigma 18-250mm lens.This will fit both the Canon and Nikon cameras—you just specify the mount. The maximum aperture is f/3.5–f/6.3, but it has an incredible range of focal lengths, it’s not expensive, and it’s light. Canon has an 18–200mm f/3.5–f/5.6 that is also a good choice. Note that while the Canon lens goes to 200mm instead of 250mm, it has a larger maximum aperture at the full telephoto position: f/5.6 instead of f/6.3. Buying a lens is really all about compromise between cost, focal length, and maximum aperture.

If you are extremely budget conscious, the Tamron 55-200mm f/4-f/5.6 zoom is a good choice. You will forego the wide angle end of the spectrum, but you can always add another lens in the future. If you love shooting sports and wildlife, Tamron also makes a 70–300mm f/4–f/5.6 that can fit into any budget. This lens will even do close-up photography. (Note: Manufacturers often update lenses and specifications, so check current listings. You should find offerings similar to what is mentioned here.)

Wish List

For maximum creativity, you need a wide range of focal lengths. In the ultra wide angle range I recommend somewhere in the 14–16mm range like the fantastic 14–24mm Nikon lens, the Canon 14mm fixed wide angle, or the Canon 16–35mm II. These are not inexpensive lenses, but they give you the ability to take truly dramatic pictures like you see in (#11, #12, and #13). Later in this issue is a section on using wide angle lenses creatively, but for now you can see that they give you a unique and compelling perspective.

The telephoto side of the spectrum is best covered with two different lenses. I feel that a medium telephoto is important, such as a 70-200mm. This is what I have. I bought the 70-200mm f/2.8 and my wife has the 70-200mm f/4. While I have that coveted large maximum lens aperture, my wife’s telephoto lens is much lighter than mine and significantly smaller. This is important to her because she is petite and can’t carry the weight that I am willing to carry.

A longer telephoto for sports, wildlife, and birds is invaluable. Nikon has an incredible 200–400mm zoom, which is extremely versatile and very sharp. Canon has a 300mm f/2.8 and a 300mm f/4, both of which are great lenses. I have the 500mm f/4, which has produced the best pictures of wildlife and birds in my collection. It’s very expensive, but it’s worth every penny, in my opinion.

For macro photography, there are a number of choices. I carry with me the 50mm macro lens, which is quite inexpensive as lenses go and, at the same time, it’s very small and light. Many photographers like a telephoto macro because of the sense of compression and the fact that the out of focus background is completely undefined. The 100mm macro is a great lens and so is the 180mm macro. I go into macro lenses and accessories later in this issue.