Business Trends

The Digital State Of Stock Photography; Will Digital Replace Film As The Image Medium Of Choice?

To answer some current technical questions on the digital aspects of the business

side of stock photography, we talked to three industry veterans: Rohn Engh of

PhotoSource International (www.photosource.com),

Rick Rappaport, owner of Rick Rappaport Photography (www.rickrappaport.com),

and Ron Rovtar, managing editor of The Stock Asylum, LLC (www.stockasylum.com).

Each has a different perspective based on their specific business models.

PhotoSource International matches the photo needs of buyers with the photo collections

of editorial stock photographers. They are in the forefront of an important

change in the way stock photo clients search for images--from looking at

images to using a "text search" to find the exact picture they need.

This could be less costly and more time-saving. Rick Rappaport owns a photography

studio and has been an advertising photographer for over 20 years and shoots

assignment and stock. The Stock Asylum is an editorial outlet and publisher.

With all the recent changes in the stock industry, a good part of their effort

is to help stock photo buyers make sense of rights-managed purchases. Though

they are currently a trade publication, they will be adding several resources

to help buyers search for the right stock image.

Shutterbug: What is the most recognized or common standard

today for digital file size and submission for stock photography?

Rohn Engh, PhotoSource International: We deal in the area of editorial stock

photography, so my remarks might not be universal to all stock. Our smart and

successful editorial stock photographers don't stray out into areas that

are going to require big budget equipment. We all know that most buyers in the

book and magazine field like to see a physical file size to print an 8x12 at

300dpi. But there's always the exception. A touching scenic or impromptu

shot taken while on vacation with your 5-megapixel camera just might fill the

bill of a harried editorial photo buyer.

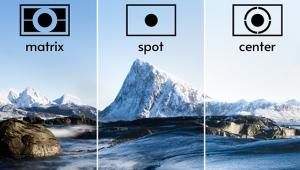

Ron Rovtar, The Stock Asylum: If one is submitting images for

consideration by a stock distributor, just about anything that a computer screen

will render at 6 or 7" on the long side will do. These can be JPEG files,

usually compressed at one of the better quality settings. For consideration

by the clients, designers, and art directors, similarly small image files are

usually acceptable. Most stock distributors provide these kinds of low-resolution

images for comping and they are usually adequate for most decision making in

the early stages of a project.

It gets trickier when supplying a final version for submission to either a distributor

or a client. Many distributors now require 50MB image files in an RGB color

space. The final color space (sRGB, Adobe RGB, etc.) can vary from one distributor

to another. Some, like Getty, convert to their own color space, I am told. These

images are almost always 8-bit images, but it is becoming more common for photographers

to scan (or shoot) at 16 or 14 bits, make major adjustments, then reduce to

8 bits per channel. This avoids a histogram with gaps, which can cause the technical

folks to panic a little.

Uncompressed TIFF files are usually acceptable. Whatever format is used, there

should be no extra layers or channels. Sharpening should be kept to a minimum

or left to the distributor or client. Some folks go pretty crazy when they get

an over-sharpened image. One place where some sharpening can be needed is when

you have significantly reduced the size of an image file. For some reason, we

have found, these images can appear very soft, even when the high-resolution

version is tack-sharp.

As for supplying images directly to the stock photo clients, two points should

be mentioned. First, photographers who are not well-schooled in pre-press concerns

should avoid supplying CMYK files. I think there is an assumption by clients

that CMYK files are ready to go on press. Making images press-ready is a tricky

piece of work if you don't know what you are doing and clients can get

quite upset when the images don't print right. Some photographers are

getting up to speed here, but it is still an added risk. My advice is that if

you don't fully know what you are doing, stay away. If you do, make sure

you are paid for the extra effort and risk.

The second concern about supplying files to clients is to make sure you do not

supply files very much larger than they need. It is unfortunate that a percentage

of buyers willfully try to cheat photographers and agents by understating press

runs and the size of the final image. Most clients are honest, but there are

enough dishonest ones out there that this is a concern. I have even heard stories

of clients who brag about their dishonesty to photographers. Anyway, the general

rule has been that you need about twice as many pixels per inch as printed dpi.

Shutterbug: With the new Nikon and Canon cameras that can deliver

36MB or 48MB plus files right from the camera, do you see this technology eliminating

the need to shoot film and scan for stock photography submission?

Ron Rovtar, The Stock Asylum: Eventually it will and many photographers

have already made the jump. However, while I have not made this transition myself,

I have been around and talked to enough shooters to know that there is a steep

learning curve here. Any photographer getting into digital cameras should hold

onto his/her film equipment until she/he feels very comfortable with shooting

digital. One of the biggest problems with digital right now is that so many

people have incredibly firm, though sometimes very conflicting, ideas about

what they want. First of all, this is all very new to a lot of people. Secondly,

we have an unusual situation in that we have a lot of technical people at stock

distributors, ad agencies, printers, and design firms who are making decisions

about what are essentially photographic concerns. Many of these people, even

at the biggest agencies, printers, and distributors, spend a lot of time viewing

images at the pixel level rather than simply standing back and seeing the image

itself. It is the old "not seeing the forest for the trees" sort

of thing. Unfortunately, it is a reality, and will be for some time.

Rohn Engh, PhotoSource International: I'd rather hedge

my bets. Investing in "bigger and better" doesn't mean the

stock photo buyer is necessarily equipped to accept what you have to submit.

He/she might choose to send your file or transparency through to their local

service bureau anyway. First consideration is to find out what your stock photo

buyers accept in the way of files or originals.

Shutterbug: How acceptable to the end-client is it for stock

photographers to go directly digital without shooting film and scanning for

stock photography?

Ron Rovtar, The Stock Asylum: I think this varies widely depending

on the client. Truth is, I think the majority of clients rely on the photographers

and the stock distributors here. Of course that means that the photographer

or distributor gets the blame if something goes wrong and that can cost down

the road. While many buyers don't seem to know the difference (or care,

for that matter) I have heard of some backlash where buyers have had such bad

experiences that they will not accept digital at all.

Rick Rappaport: Most people understand it's going to

be scanned anyway so why not "save" the money and time and receive

digital captures right out of the camera. The problems and complications of

digital workflows both for photographers and clients is the subject of many

intense workshops. Suffice it to say that digital captures are far more time

and capital consuming for the photographer than film. I did have a client, still

do by the way, who was so used to seeing transparencies on the light box that

he wouldn't accept digital files without quite a convincing economic and

quality "workshop" from me.

Rohn Engh, PhotoSource International: Since the digital revolution

is not slow-paced, the chore of both learning the new technology ("I just

read about it this morning...") and learning the changing needs of

photo buyers is taxing. Editorial photographers, luckily, deal with a small

nucleus of photo buyers. Usually, their photo buyers' technical needs

mirror each other. When one photo buyer changes, the others usually are not

far behind.