What Makes Soft Light Soft?: It’s More About Basic Geometry Than Anything Else

For decades, soft light has been the bee’s knees for portrait photography. It’s flattering, pleasant to look at, and undistracting.

But what makes soft light soft, anyway? Is there some secret ingredient in those big, boxy fixtures that tame otherwise hard and harsh photons, causing them to fall more gently on the face of your subject?

Of course not. Soft light is strictly about geometry. It’s nothing more than light coming from multiple directions, thereby reducing the contrast between fully lit subject areas and shadows.

Consider a simple example. A model has come for a portrait that will launch her fashion career. You build up lighting a piece at a time, using what a physicist would call “point sources.” In a studio setting, these are just very small lights. Putting this light in front of your model’s face and off to one side, you’ll note that while most of the subject is more or less uniformly lit, facial topography such as the nose and eye sockets are not. The shadow cast by the nose interrupts the smooth tones of the model’s skin by being completely dark. The contrast ratio between her cheeks and the shadowed area is infinite—which obviously thoroughly trumps the dynamic range of your expensive DSLR.

The result is a contrast ratio higher than Everest. A print made using this setup would have black areas appearing like holes in her face, as harsh as lye soap and guaranteed to deep-six your model’s aspirations to grace the cover of Vogue.

But now add a second light, a bit closer to the centerline of this setup (the imaginary line extending straight out from her nose). Obviously, this doubles the light falling on the subject. But the nose shadow from the second light is a little shorter. Sure, the cheeks are now twice as bright, but some of the original nose shadow is half filled in by the second light, so the contrast ratio (highlight to shadow) is two to one. The (now thinner) shadow area closest to the nose is still completely dark. But there’s an overall reduction in contrast ratio.

You can imagine what happens as you add more small lights: the shadow becomes smaller and softer, and its edge feathers gently into the fully lit areas of the face.

Clearly, it’s the fact of having an extended, non-point-source light fixture that achieves this result—and hence the effectiveness of large luminaries such as LED arrays, umbrellas, and softboxes. In Hollywood’s heyday, their equivalent in exterior photography was a cheesecloth scrim. These would turn brutal sunlight into a softer illumination to flatter John Wayne’s corrugated physiognomy.

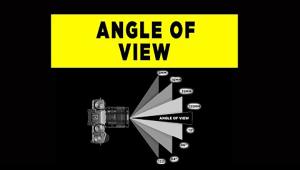

Size matters, but it’s only half the story. Move your luminaries to greater distance, and the shadows go back to being narrow and hard-edged. The farther from the subject, the more the array mimics a single light.

So it’s not the actual size of your softbox (or umbrella or whatever) that does the trick, but the apparent size. How big does the light source appear from the position of your subject? Typically, your fixture should be no more than three times its width from your subject. In other words, a 24-inch softbox will work best at six feet or less from the model. Even a monster 60-inch softbox won’t be soft if it’s near the back wall of the studio. And a four-inch, white diffuser on your camera flash will, despite your fervent hopes, produce lighting as hard as a plywood mattress.

Also, don’t confuse soft light with light of reduced intensity. Dreamy moonlight is low brightness, true. But the moon is a hard light source. And it’s not the color temperature of the source that tames light either. Sure, you may prefer the yellow-red pallor of candlelight. But a single candle is also a hard light source.

Mind you, soft light isn’t invariably best. Consider the luscious look of studio-shot movies of the 1940s and ’50s. Not many softboxes there; just carefully balanced, multiple hard sources that sculpted faces in a controlled range of highlights and shadows. But photography back then was largely black and white, and tonal separation was the only way to give the subjects depth. Today, color can do much of that for you; hence the lure of soft lighting.

Bottom line? Diffusing light by itself won’t make it any softer—only dimmer. But by putting a flash in a big box with diffusing material on the front, and thereby extending the size of the illumination source, light from a tiny flash tube can be as flattering as a north-facing window.

Seth Shostak is an astronomer at the SETI Institute who thinks photography is one of humanity’s greatest inventions. His photos have been used in countless magazines and newspapers, and he occasionally tries to impress folks by noting that he built his first darkroom at age 11. You can find him on both Facebook and Twitter.

Editor’s Note: Technically Speaking is a new column by astronomer Seth Shostak that explores and explains the science of photography.