Pioneering Photographer Dan Burkholder Discusses His Techniques and His Vision

The recent book Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 is a groundbreaking survey of significant work and ideas by imagemakers who have pushed beyond the boundaries of photography as a window on our material world. These artists represent a diverse group of curious experimentalists who have propelled the medium’s evolution by visualizing their subject matter as it originates from their mind’s eye. Many favor the historical techniques commonly known as alternative photographic processes, but all these makers demonstrate that the real alternative is found in their mental approach and not in their use of physical methods.

Within this context, photographer and photography historian Robert Hirsch outlines the varied approaches these artists have utilized to question conventional photographic practices, to convey internal realities, and to examine what constitutes photographic reality.

Hirsch explores the half-century evolution of these concepts and methodologies and their popularity among contemporary imagemakers who are merging digital and analog processes to express what was thought to be photographically inexpressible. —Liner notes supplied by publisher.

Process is often as or more interesting than technique. And while the artists shown and interviewed by Robert Hirsch in this fascinating book certainly vary widely in technique and their use of photography within their work, it is in their way of thinking and approaching the use of the image that is most revealing, challenging, and, I think, inspiring. The images, essays, and interviews in this book offer a survey of the developments in application and vision of many such artists over the last 50 years. Hirsch’s interviews cover process, but perhaps as important he gets quite deep into the rationale and often struggle of each artist as they developed their vision. He also places that vision within the legacy of those who came before and the context of those who work today in stretching photography’s bounds. A must for students and libraries, a great read (with excellent image reproduction) for anyone into the art and craft of photography. Here’s an excerpt from the book, an interview with Dan Burkholder. —Editor

Dan Burkholder

• MS Brooks Institute, 1991

• BA Brooks Institute, 1980

www.DanBurkholder.com

Although classically trained at Brooks Institute of Photography, Dan Burkholder (b. 1950) came to photography from a radically different background, having spent time in a federal prison as a Vietnam War resister. Burkholder’s book Making Digital Negatives for Contact Printing (1995) pioneered the melding of digitally-enlarged negatives with historic non-silver processes, such as platinum/palladium and pigment-over-platinum, to gain more artistic control over the outcome. His book The Color of Loss: An Intimate Portrait of New Orleans after Katrina (2008) presents a hyper-realistic account of the devastation suffered by the city and its residents from within the damaged interiors. Through his innovative management of High Dynamic Range (HDR) imaging, which renders extensive detail in both the highlights and shadows of the final print, Burkholder pointedly juxtaposes beauty and destruction in wide-angle perspective photographs that deliver an intense, tactile sensation of the chaos and loss evident in the storm’s aftermath.

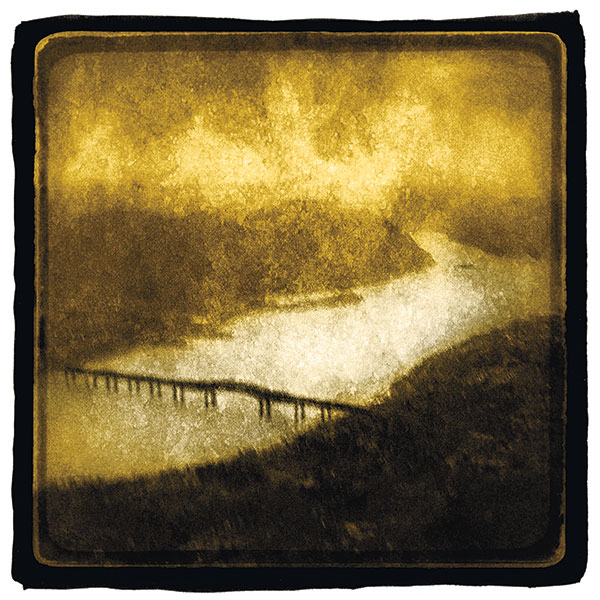

In a time when everyone with a smartphone can consider themselves a photographer, Burkholder’s iPhone Artistry (2011) details how he captures and processes his images on-location, in the manner of plein air painters, with an assortment of inexpensive imaging applications. According to Burkholder, “For the first time we have both camera and darkroom in the palm of our hands.” However, Burkholder reverses the typical electronic workflow by converting a digital image into a handmade one. After in-camera processing, he enhances the digital image through an analog printing process that entails hand coating thin, vellum paper prints with platinum/palladium sensitizer and 24K gold leaf that fuses the subject’s skin with his mind’s eye interpretation of it. Such work that brings a pictorialist-style physicality to the digital image corresponds with his philosophical artistic approach. Burkholder states, “I am more concerned with emotional honesty than literal honesty in my photographs. My job is to respond to visual intrigue and beauty, and then to create a photograph that conveys to the viewer my feelings for the subject.”

Robert Hirsch Interviews Dan Burkholder

Tell me what you do and why you do it?

With the exception of the New Orleans work, where I wanted to show how nature and government had conspired against the citizens of New Orleans, visual intrigue and beauty are the two things that most interest me. Years ago, when I was a draft resister during the Vietnam War, I wished I could bring more socio-political concepts into my work. I realize now that, no matter what politics I feel outside of photography, the images I create will almost always be politics-free.

Why do you interact with what the camera records?

The old notions of photographic reality are not complete enough for me. Like many others, I use the captured image as a launch pad for the creative post-processing steps that lead up to the finished image.

What do you think about postvisualization?

There are people who will say, “You should never post-process an image.” Years before I had a computer I would use diffusion under the enlarger lens. I would put cellophane or a black stocking stretched on a cardboard frame and use it under the enlarging lens to diffuse the light and make the shadows spread and make the print highlights glow. These and a plethora of other darkroom techniques were all post-processing, so to suggest that post-processing is not photographic is complete horse manure.

What qualities make your work stand out?

Among other characteristics it’s my reluctance to rely entirely upon contemporary printing methods. In my latest platinum/palladium on vellum over gold leaf, I’m grinding palladium leaf with gold to create split tone effects. As beautiful as the archival inkjet print is, we certainly don’t want a photographic world in which every print is inkjet, do we?

No matter what the printing process, I return to my landscape roots. Even the iPhone work, though infused with a texture and palette all its own, carries on the landscape theme that has weaved in and out of my portfolio for decades.

One of the curses of our medium—something we always run into all the time—is that non-photographers look at a photograph and say, “I can do that.” The real point is, yes, you could have done that, but you didn’t. You could have been a brain surgeon, but you didn’t take that course in life. So, yes you could possibly have made the photograph, but you didn’t.

That’s what separates the creative person from the non-creative person, not the ability, but the stamina, goal orientation and—dare we say it—talent.

Once my mother stopped by when I was retouching a platinum print on an old, tilted drafting table, and she said, “You look just like your grandfather,” who had been a draftsman. Now I’m sitting at that same table doing this platinum on vellum over gold leaf work. Yesterday I flipped down my high magnification magnifiers and using a tiny brush with eight hairs, painted in the gold in just the right place to create a split tone effect. My mother’s comment resonates when I do such work. I feel a shared sense of aesthetic kinship and attention to detail with my ancestors and hope they’d be proud.

When people see these gold prints, they aren’t moved to declare, “Well, I could do that.” They know right off the bat they aren’t going to do that and that they won’t make the effort to learn how. In terms of materials and control of the medium, it puts me in a private castle.

Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 (ISBN: 9780415810265, 256 pages, $49.95) is available for purchase on FocalPress.com, Amazon.com, and BN.com.

What has most influenced your work?

My prison experience in the early 1970s—refusing induction, turning in my draft cards—that gave me a moral anchor. It’s nice to know when you’ll say no, that you’re not going to be a part of something. That experience has given me a certain amount of moral strength throughout my career. How has that experience interfaced with photography? A certain amount of hardship in life broadens the experience spectrum.

No matter how bad times get, I think, well, it could be a lot worse. They’re not going to send me back to prison for being playful in the classic or digital darkroom or for using an iPhone instead of a larger camera. So in terms of your life, you are a little more willing to try things. You have a wider range of experience to reference.

About The Author

Robert Hirsch is a photographic imagemaker, historian, and writer. Former executive director of CEPA Gallery and now director of Light Research in Buffalo, New York, he has published scores of articles about visual culture and has interviewed many significant photographers of our time. His books include Light and Lens: Photography in the Digital Age; Exploring Color Photography: From Film to Pixels; Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Equipment, Ideas, Materials, and Processes; and Seizing the Light: A Social History of Photography. A former associate editor for Digital Camera (UK) and Photovision, Hirsch is a regular contributor to Photo Technique. He has also written for Afterimage, exposure, History of Photography, The Photo Review, and World Book Encyclopedia, among others. He has curated over 200 exhibitions, and had many one-person and group shows of his own work. For more information, visit www.lightresearch.net.