Luminary: An Exclusive Interview with Photo Legend Albert Watson

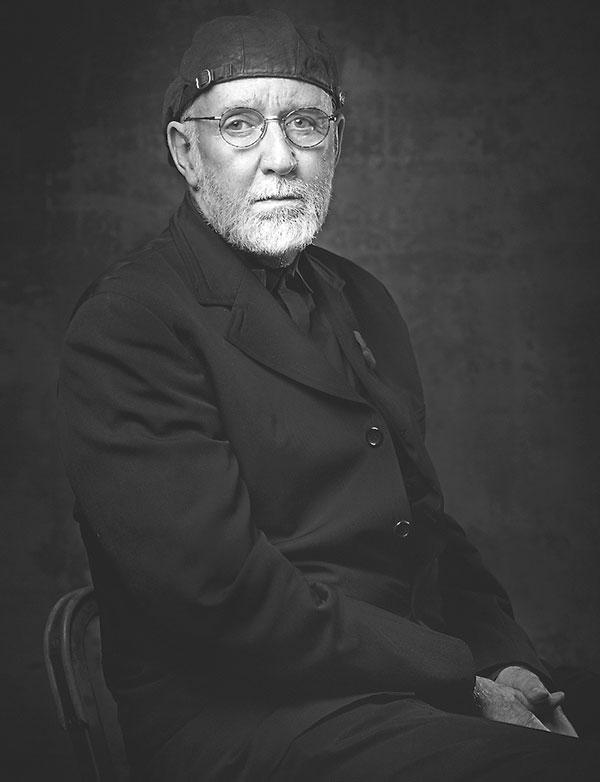

Scottish photographer and living legend Albert Watson is no stranger to accolades. Earlier this year, Watson was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Queen Elizabeth II for his contributions to photography.

Renowned for his fashion, celebrity and art photography Watson has also been named by Photo District News magazine as one of the 20 most influential photographers of all time, joining a pantheon of imaging luminaries that includes Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. In his long and storied career, Watson has shot over 100 Vogue covers, 40 Rolling Stone covers, published several books, is collected in museums and has had dozens of gallery shows.

Today at 73, Watson remains as prolific as ever with a major exhibition of new work in Zurich and a new book of landscape photos in the works. In this exclusive interview with Shutterbug’s Steve Meltzer, Watson talks about his life, his photography, and working in the modern digital world.

Q&A

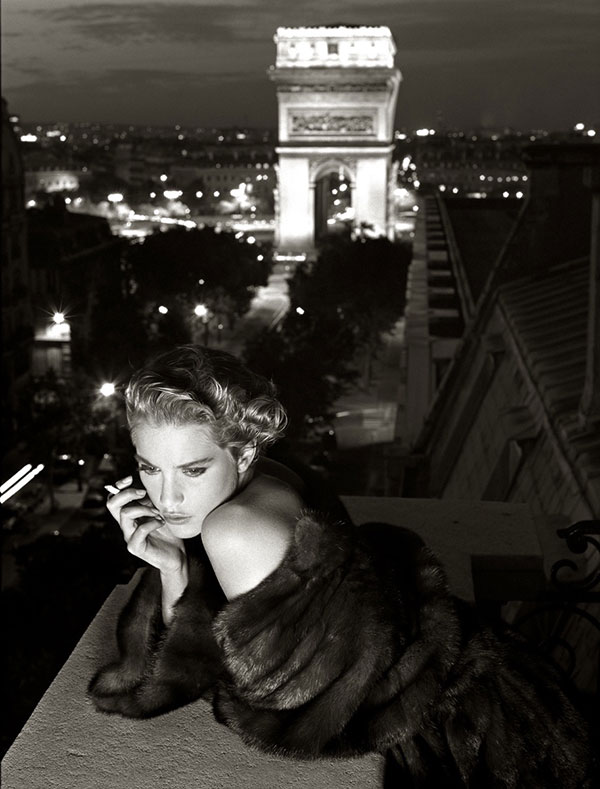

The first question I put to Albert Watson was what made his photographs different; what gave them their impact? After a moment Watson responded that he felt that the key to his images was that they appear very straightforward and are as he put it, “easy to look at.”

“But there is a lot going on in them once you really look,” he said. “All my work is graphic, conceptual and cinematic and whenever I shoot I always try to see just how intense I can make the image.”

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1942, Watson has been blind in one eye since birth, but that hardly stopped him from pursuing a career in visual arts. He studied graphics and art at the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee, then went on to the Royal College of Art in London where he studied film and television and took his first photography classes. The combination of graphic, conceptual and cinematic elements is a result of this education.

Watson’s career began when he and his wife Elizabeth settled in Los Angeles in 1970. She found work as a teacher and he began taking photographs. That same year he encountered a Max Factor art director who offered him a photo "test" session. The session went well and two of Watson’s images were purchased. He began getting noticed and getting assignments from magazines like Mademoiselle, GQ and Harper’s Bazaar.

In 1973, Watson took his first celebrity portrait for Harper’s Bazaar’s Christmas issue. He was assigned to photograph the movie director Alfred Hitchcock for a feature about “celebrity chefs.”

Hitchcock loved to cook and Watson was supposed to shoot him with a finely prepared Christmas goose. But Watson decided that rather than shoot “Hitch” with a cooked goose it would be more fitting to have him holding up a dead goose by its neck. This image became one of Watson’s most well known and last year it was one of the “iconic photos” reshot by photographer Sandro Miller with the actor John Malkovich portraying Hitchcock.

As a former cinema student, Watson asked Hitchcock about his style of work and about storyboarding during their photo shoot.

“Hitchcock said that once he had storyboarded a film, the film was done,” Watson recalled. “I asked if that meant that he wouldn’t use anything unplanned, like an actor adlibbing a good line. His response was that he would shoot it but he would also shoot what he had storyboarded and then use the best take. In other words planning doesn’t exclude spontaneity.”

With the success of the Hitchcock photo, Watson went on to shoot thousands of portraits of movie stars, supermodels, rappers, rock stars and, of course, the Queen of England. While discussing his portraiture work, I asked Watson about his approach to capturing his subjects.

“Planning and preparation are essential to this type of photography,” he said. “With celebrities I spend time reading about them and planning out how I will approach them. For example, Al Pacino was recently here (at Watson’s N.Y. studio) and I found out that he likes a certain kind of espresso served with a slice of lemon peel.

“I had one of my assistants find the coffee and when Pacino arrived I offered him a cup. He was delighted that I had taken the time to make this small gesture and it allowed me to start a conversation with him.

“I think that the photographer’s best weapon is their own personality. I love to meet people and to spend time chatting with them before I start to make photographs. It puts them at ease and it gives me clues to their personalities.”

Connecting with His Subjects

This ability to connect with his subjects helps explain Watson’s impact on portrait and fashion photography. Establishing relationships with his subjects he gets their participation in the shoot and their trust lets him push the intensity of the shoot.

“Diana Ross is a well known diva and I needed a way to connect with her. I found out what her favorite flowers were and had a lot of them in the studio. I didn’t say a word about them, just let her discover and enjoy them. She appreciated it and it helped her to feel comfortable with me and for me to get very intense and special images.”

I asked next what he thought of celebrity photographers today.

Watson said that he was dismayed by the unprepared, unplanned “hello/goodbye” style that he feels is prevalent. As an example he recalled one of his own experiences. He was hanging a gallery show and a local magazine wanted to take some photographs of him. He agreed and when the photographer arrived Albert asked him to wait for a few minutes while he finished hanging the show. Once he was done he asked the photographer what he would like to do. The photographer’s response was “I dunno.” Albert was stunned that the photographer had no plan.

New Gallery Show

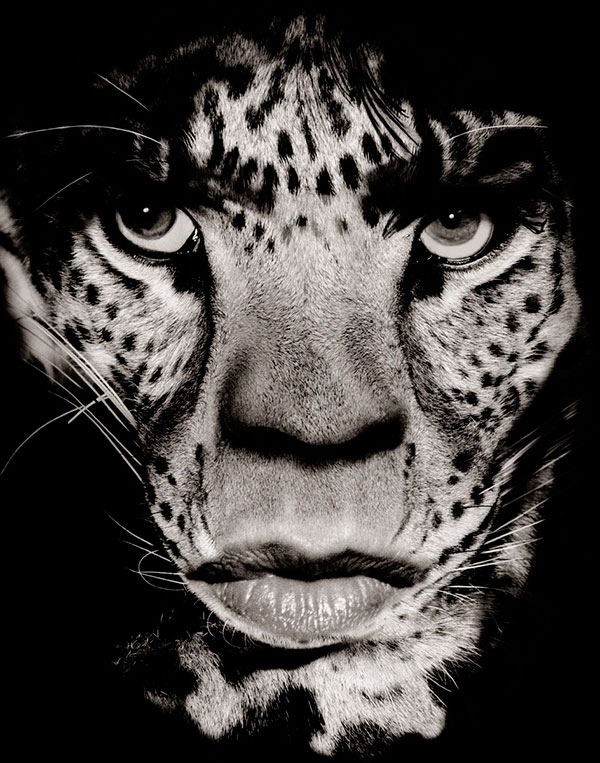

Speaking of gallery shows, Watson was very excited about an exhibition of large prints – and some older images – at the Christophe Guye Gallerie in Zurich (Now until October 25, 2015.)

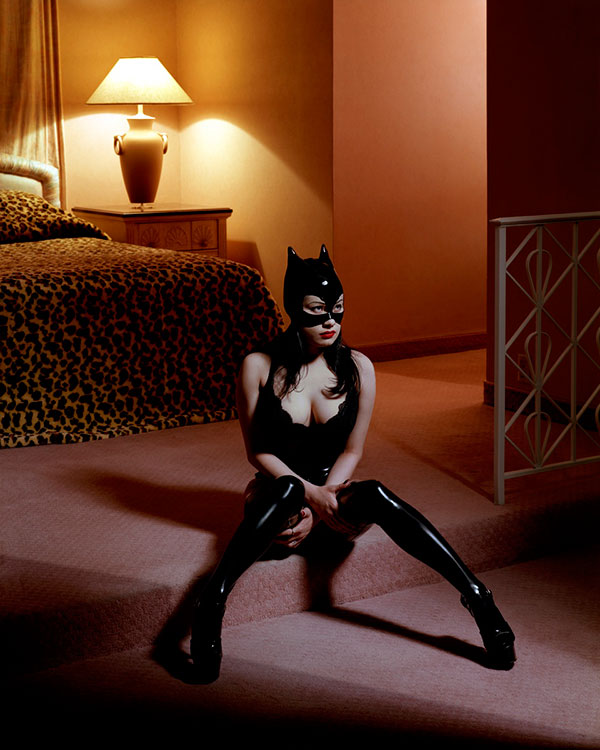

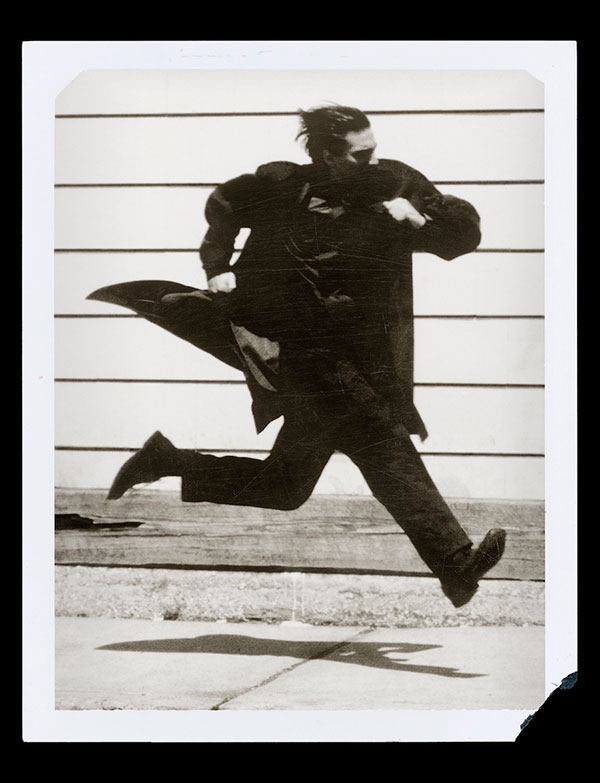

Called “ROIDS!”, the show features supersized 6x8-foot blowups of some of his 2 ¼ and 4x5 Polaroid prints taken with Polaroid backs on his Hasselblad and Horseman 4x5 cameras.

With the two cameras, he shot over 100,000 Polaroid images. His first idea for the show had been to scan the Polaroid prints at 800 or 900 DPI and make conventional 16x20-inch prints. But looking at the 16x20s he became interested in how the surface of the Polaroid print itself became part of the image. Curious about this he rescanned the images at 9000 DPI to see what would happen at this resolution.

“The result was wonderful because at the higher resolution, the Polaroid surface became an integral part of the prints. I liked the roughness of the acetate surfaces, the traces of fingerprints, the tears and the scratches that all had become visible in the 6x8-inch prints. It was like looking at a Polaroid through a microscope.”

While discussing his new work, I told Watson that photographers such as Arthur Tress and Larry Fink had told me that their classic images, those taken from about 1960 to 1990, sold better than their contemporary work. I asked him if he had experienced something like this as well.

“Yes. My work from the 70s, 80s and 90s is very much in demand, more so than the contemporary work.” As an example, he mentioned the 2007 sale of the 1993 photograph of supermodel Kate Moss for $108,000.

“However I try to keep my feet in both the vintage collectible market and the contemporary art market. A gallery like Christophe Guye, for instance, is willing to show new work, while others just want vintage.”

Landscape Work

Watson is a very prolific photographer whose idea of getting away from his studio is to work on some photographic project. His latest effort is an extensive exploration of Scotland’s Isle of Skye.

He had spent time there as a child with his parents and loved the place’s mysterious landscape. Returning to Skye for the first time in 25 years, he took hundreds of photographs of the rain and mist shrouded land for a soon-to-be published book from Taschen. (The BBC did a wonderful documentary about Watson’s photography on the Isle of Skye and you’ll find links to it at the end of this article.)

Albert organizes his landscape work as meticulously as he does his studio photography. With the Isle of Skye project he thought long and hard about the images he wanted and the feeling he was looking to capture. He said that he had words in his mind like desolation, strangeness and romanticism, and he added even, “A touch of the 'The Lord of the Rings.'”

But talking about landscapes Watson had a caveat for landscape shooters. “Most photographers, they get sucked into the landscape and the landscape dominates them. But, you have to make sure that in the end you dominate the landscape.”

Back to the Darkroom

We had been chatting for quite a while when Watson said, “I’m going to have to leave you soon because I have to go into the darkroom to make a print for a client.”

“Darkroom?” I said.

“Yes, I do my own printing. I tried for years to find a good lab but I was always faced with having to go though the filter of someone else’s ideas.”

“Printing my own prints I am in total control. I can decide how to print an image and how much exposure to give a particular part of it and so on. When I see the print, I can make adjustments immediately. I can’t do that kind of print and reprint with a lab because it is too time consuming and they don’t like the small changes I want. I also keep everything I print because I know that one day I might look at these ‘bad’ prints and see them in a different way.”

This led me to ask where he stood on the film versus digital debate. “For me digital doesn’t make a big difference, I shoot both film and digital. I like film because it has a certain 'accent' to it while digital gives me choices. The computer has opened up a thousand possibilities for the photographer but I think that darkroom experience is what gives you the ability to work on the computer.”

“But the computer has also introduced an element of laziness. I see so many photographs that are badly Photoshopped. In a fashion photo every bit of the model’s skin will be ‘‘shopped, but when you look closely at the highlights in her eyes you see the studio, the flashes, the photographer and the art director. No one has taken the time to fix that.”

Continuing, Watson added,” Photography requires discipline. To have a great photograph requires a combination of what you take and how you present it. This is what makes a beautiful photograph; the ability to capture both the magic of the moment and the magic of the print.”

(Special thanks to Aaron Watson for all his help with this story. All photos courtesy of Albert Watson.)

To see more of Watson’s work, visit his website.

For a look at Watson working on the Isle of Skye photo project, check out these videos: