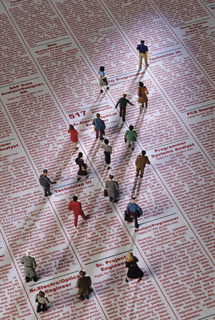

“Stock Shock”; Big Changes In The Picture Business

The stock photo business—making images on speculation and then attempting to match the image to a buyer—has seen major changes. The traditional business model of the stock agency serving as a photographer’s agent has shifted to the picture library model. Other changes have included companies hiring staff photographers to create stock—as opposed to using outtakes and spec shots—and radical changes in the agency’s contractual relationship with free-lance photographers.

Perhaps the most radical change has been in the way Internet access to images changed the way photo clients could purchase stock. Soon after the online stores opened we saw different pricing structures: rights managed, royalty free, subscription, and microstock. This last change, the microstock model, seems to be creating the biggest shock in stock, so we thought it was time to give our readers an overview of industry changes as seen by professionals in the field. Stock photography is far from dead, but it remains to be seen what type of phoenix rises from the ashes left by setting the traditional models afire to create something new.

|

|

|

I want to thank stock photo consultant Ellen Boughn (www.ellenboughn.com) for her thoughts in helping me construct this article and the photographers we interviewed for their time, energy, and attention. These folks were most helpful in their ideas and comments:

• Ed Bock (http://edbockstock.com)

• Shannon Fagan (www.shannonfagan.com); Fagan is also president of the Stock Artists Alliance

(www.stockartistsalliance.org)

• Paul H. Henning (www.stockanswers.com)

• Michal Heron (www.allworth.com/category_s/93.htm)

• Jim Pickerell (www.selling-stock.com)

Shutterbug: We have seen a few stock businesses close their doors recently and some photographers were badly hurt in having their images lost or discarded or in the case of bankruptcy not getting paid their owed royalty fees. What do you think went wrong in the industry for these firms and their photographers?

|

|

|

Jim Pickerell: There are several factors involved. Point 1—The image choice and marketing muscle offered by the mega agencies have made it increasingly difficult for smaller agencies to get their product seen and thus compete. Some have been able to work out deals to have some of their images represented on the major portal platforms. Others have been acquired and many of those who haven’t been able to do either have seen a steady decline in revenue.

Point 2—In order to license rights to an image it has become absolutely necessary that the image be available for research online and also deliverable as a high-resolution digital file. This has severely impacted all those photographers with images shot on film because in most cases it is not cost-effective to digitize most of those images. Agencies that were dependent on film files have seen a rapid decline in revenues.

Point 3—There is a huge oversupply of images. With digital capture photographers can create a lot more images faster. However, for several years there was no increase in the number of buyers, or the number of images needed by the traditional customers. Recently, we are even seeing a decline in the number of still images needed. So we have the classic supply/demand problem.

Point 4—Then we introduce microstock. There is no question that microstock has opened up a great new market and found a lot of new customers who simply couldn’t afford to pay anything approaching traditional prices for the images they wanted to use. For example, iStockphoto made about 25 million individual sales of images in their collection at an average price of about $6.50 per image. I have talked to several of the more productive iStock photographers who agree that they get around $1.30 per image downloaded and that they receive 20 percent of the gross sale. Thus, $1.30x5 = $6.50 gross sale price. This is about the price of a median size file (approximately 2000x1500 pixels), which is the most popular size at most microstock companies. Commercial customers pay the same as everyone else for the microstock images they buy. Commercial customers used to pay an average of $250 for royalty free and $500 for rights managed. Now they can often get the images they need for something in the range of $6.50. As a consequence, traditional sales are disappearing at a fairly rapid pace.

|

|

|

Michal Heron: I think it is a combination of plummeting prices and bad business practices on the part of the agencies. The temptation to use the photographer’s cut of stock fees as part of the agency cash flow left everyone high and dry when the income stream slowed down. Photographers should have been able to depend on agents to guard their royalties and some astute photographers avoided that pitfall by staying involved and checking payments, reviewing the books for invoiced photo uses, and watching to see when the payments came in.

Shannon Fagan: Lack of transparency is a problem. It is not fair for business-to-business operations to purposely hold back information that could adversely affect the success of the businesses that operate alongside the larger business entity. Nearly overnight business owners who relied upon these licensing entities were thrown into a tailspin, but the public relations from weeks prior did not match up with the facts of what occurred. You cannot be experiencing “sustained growth and meeting expectations” and then go bankrupt three weeks later.