Playing With Perspective

Go Wide Or Get Stacked

We judge near and far, big and small by our innate sense of perspective. A sort of visual grammar, it orders the world around and ensures that we can get where we're going and that when we reach out to touch we'll have a tactile rather than virtual experience. In photography, and all visual arts, the relationship of foreground and background is established by the relative size of subjects within the picture's two-dimensional plane. |

|||

Much of what determines our sense of a scene's perspective is the lens we use to create the image. So-called "normal" lenses, such as a 50mm in 35mm format and an 80mm in medium format, are called just that because they order perspective in a way that is close to what we see. But when we use very wide angle or long telephoto lenses, combined with a particular point of view, we can skew that normal sense of perspective and create another way of looking at a subject or scenes. For some, such as architectural photographers, that can result in unwanted distortion. This can be corrected with camera movements or special lenses, known as PC (or Perspective Control) lenses. But one person's distortion is another's creative point of view, and that's where creative use of long and short lenses comes into play. |

|||

A Sense Of Space |

|||

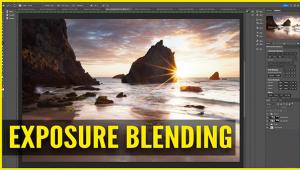

To compress space, make use

of the narrower angle of view of long telephoto lenses to stack subjects

together. The effect is a flattening of the image plane and is an excellent

way to enhance repeating patterns, group similar subjects, or play with

the juxtaposition of one environment with another. Telephoto lenses can

also be used to create abstractions from larger subjects, such as buildings

or long-distance landscape views. They can also be used to isolate distant

subjects so that other visual effects, such as aerial perspective, can

be brought into play. This relies on light values rather than just size

relationships to yield a sense of scale. |

- Log in or register to post comments