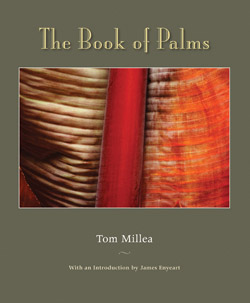

Personal Project: Tom Millea: The Book Of Palms: A Self-Publishing Saga

After almost 40 years of making platinum prints, chemical fumes had harmed Tom Millea’s lungs to a point where he could no longer go into the darkroom. He says, “Closing my studio was traumatic in the extreme.” He didn’t believe that anyone else was capable of printing his work as he envisioned it. He liked computers but had no desire to try to make digital prints look like his platinum prints. “One technique could not replace the other,” he says. He selected prints from his inventory to sell in gallery shows and considered himself retired.

After almost 40 years of making platinum prints, chemical fumes had harmed Tom Millea’s lungs to a point where he could no longer go into the darkroom. He says, “Closing my studio was traumatic in the extreme.” He didn’t believe that anyone else was capable of printing his work as he envisioned it. He liked computers but had no desire to try to make digital prints look like his platinum prints. “One technique could not replace the other,” he says. He selected prints from his inventory to sell in gallery shows and considered himself retired.

But by 2004, when the color palette of digital inks had changed, Millea thought his prints were beautiful, and comparable with his darkroom images. He began making digital color photographs full-time using an Epson 2200 printer. Over the next five years, he says, “By myself, step by step, I learned to use the computer to make images I felt were uniquely my own.” He eventually put together a complete digital studio with Apple computers and two Epson printers, the 4800 and the 9800. He could then make his own prints up to 40x60”.

At about that time Millea experienced a revelation: “I discovered two magnificent red banana palms in the yard of a friend and photographer, Bob Carroll, in Carmel, California, where we both live. I was struck by the beauty and elegance of these 15-foot plants, and for the next year the challenge of photographing them raised my spirits.” He started with a small Nikon F100 film camera, later replaced by a Nikon D80 with zoom and macro lenses.

Three or four times a week in all types of weather, Millea consistently photographed palm leaf details. One day, after about a year, he arrived at his friend’s home and was shocked to find that “the gardeners had cut down the banana palms when Bob was away. Intuition told me I’d barely begun my project and I was very upset because I planned to make enough images for a show or maybe a book. At the time, I couldn’t afford to buy a mature banana plant, so at a garden shop I spent two days choosing a small palm in a tub.”

Millea was yet unfamiliar with Photoshop, but he learned what he needed by himself because he has no patience with classes. When he was frustrated, he called an expert for an hour to solve problems, eventually learning Photoshop and other necessary programs.

Another year passed and then another. Constantly working now, photographing nothing but the banana plant, Millea was building a large group of images of a single subject. He exhibited prints several times in group shows but never felt the pictures could be seen well enough in that context. It was then he began thinking of a book. He had previously avoided publishing books of his black-and-white platinum prints because he felt that “the soul of a platinum print, its very essence, was lost in a book when printed on glossy paper.”

But materials had improved and he felt his images could now be printed on uncoated paper. All new color work from his printer was on uncoated paper, so it was necessary to find the right book printer who would do the job on uncoated paper, and he began the search.

At this time the select 8x10” prints Millea made were sequenced in book form in plastic pages, and he frequently re-sequenced them in alternate dummies to compare versions. He knew his final book should be more than a simple bunch of banana leaf photos, and hoped it would tell his life story in its way.

Millea asked a woman who had helped him years before on another unpublished book to help him choose images, and after months of working together the book took form, though he recalls that “sequencing was agony.”

By then he realized his book needed a suitable introduction, and he contacted numerous writers and curators in the Monterey, California area. Not a single person responded. One night he wrote to James Enyeart, former director of the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, and also the former director of the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. Millea was not optimistic because they had not connected in years, yet within three hours he received an enthusiastic and positive response from Enyeart. “That message was a profound and beautiful experience,” he states.

Here are excerpts from what Enyeart wrote: “Tom Millea is an artist who is fully aware that his photographs are abstractions of reality…with clear symbolic intent…The absorption process for him is a psychic connection with a subject in which he merges aesthetic response with ‘the thing itself,’ as Edward Weston said so aptly…[Tom’s] choice of what to photograph is always…to excite the eye.”

After four years of work, Millea still had no publisher, printer, designer, distributor, or money to finance a book. He recalled a small book a friend had self-published for $2000 and pondered ways to raise that much to self-publish. But he discovered that price was a cruel joke as he went on to spend $6000 or $7000 auditioning printers in China, Japan, South Korea, Italy, and in various American cities. “Results from all except the one in South Korea were terrible,” he reports, “partly because they rejected using uncoated paper which I required.”

Finally after more than a year he found a printer in Canada who promised to fulfill his requirements. Quite innocently, he had also looked for a publisher, and realized even if he found one, they would take over his book and make changes at will, often to save money. Besides, publishers he queried told him there was no market for his book. Millea was convinced that to create a book he could love he had to publish it himself. “In the publishing world,” he says, “unless you are already a star as an artist, you’re the last person to be listened to. I just don’t have the personality to deal with those conditions.”

He also found that distributors and booksellers do not take self-published books seriously and copies are not carried in chain bookstores. A distributor of a self-published book, if he found one, would take 20 percent of the sale price to get the book into stores, often at a 40 percent discount.

Fortunately, Millea reconnected with Joel Friedlander, his best friend in college, who turned out to be a writer and book designer. Millea says, “It was unusual to find a designer who understood how I conceived the book, and Joel knew intuitively exactly what I intended. Everything he did was perfect, right down to the glorious red cloth binding.”

By this time, though, Millea was broke. He had spent thousands on the printing proofs, and borrowed from his best friend. He knew a bank wouldn’t lend him anything. He recalled books he planned and photographed in the past, which were never published, and he dreaded another failure. At the very last minute he was introduced to Ursula Lamberson who lived in Hawaii and after a short conversation on the phone she agreed to finance the book.

They met in person a few weeks later when she came to visit, and Lamberson began to buy his fine art prints. Millea says, “This gave me a freedom I have never had.” His life changed, and he returned to interpreting his banana palm in every kind of light. He worked night and day, and when the frost came, he brought the plant indoors and found that his seeing was inspired in the new and more intimate circumstances. In retrospect, he says, “My close-up photographs were no longer simply about a banana plant. Time and place had no meaning. For six months I lived in another reality. Nothing mattered other than working with the palm.”

New images lead Millea to revise his book once more. He says, “They were far more complex than the older ones. Joel and I made new selections, came up with fewer pages, and every page in the book I feel is unique. The images became a narrative with a completely fresh impact.”

Millea prepared new digital files for a Canadian printer, and was delighted to receive proofs that looked wonderful. The printer, by chance, had a representative living 10 miles from Millea, and they met several times a week. Millea’s outlay was now at $20,000 and rising. He discovered that “paper is the main cost after the printer’s fees. Binding, covers, and other details add up fast. It’s necessary in self-publishing to know as much as possible about the process. After the press starts printing, changes cost a fortune. I advise being there when the book is printed. I wasn’t able to do that but I ordered extra proofs at every step to make up for it.”

Awkwardly, the first time The Book of Palms was printed, Millea says, “Proofs were not followed carefully and the images were too dark. When I insisted, they reprinted, but screamed and tried to intimidate me. I pointed out that the book did not match the proofs and they had to agree. Now when I see my name on The Book of Palms, I can smile.”

The Book of Palms turned out to be a work of art, the intimate exhibition Tom Millea dreamed about. It sells for $75 and is available by contacting him via e-mail at: tmillea@aol.com or by visiting his website at: www.tommillea.com.

Tom Millea has been a fine art photographer for 50 years. His first group show in the Sixties was with Edward Steichen. He studied with Paul Caponigro, and was director of the Underground Gallery in New York City in 1969. He moved to Carmel in the early Seventies, then moved to Death Valley to photograph for several years, returning to Carmel. His work is in museums around the world.