Lou Jones; The World Of Jazz

Photos © 2004, Lou Jones, All Rights Reserved

Having the good fortune to become involved wholly with an inspiration or an

idea is pretty awesome, and as long as I have known Boston photographer Lou

Jones he has been "involved." I don't think he has ever missed

an Olympics event or turned away from his deep-rooted convictions about the

death penalty in this country, producing a moving documentary in his book Final

Exposure: Portraits From Death Row.

Then there has been music and dance, above all, the era of jazz and the outstanding

musicians who lent magic to our world in the 1950s and '60s. These are

not simply "themes" or "material," they are Jones'

world. Last year I was privileged to see his work in a setting that befit the

dignity of his subjects and hear him speak of the jazz musicians he has photographed

over the years.

|

|

|

The setting was The Huntington House Museum, a magnificent restored mansion

set on Windsor Green in the heart of Windsor, Connecticut. (The kind of place

one would expect to see an exhibition of photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron.)

It was a beautiful space to show these musicians during their quiet, private,

and sometimes somber moments.

It is always interesting to me why a photographer chooses a particular theme

that spans almost an entire career. During his lecture someone asked Jones what

held him so closely to the theme of jazz. Being the inveterate storyteller he

is, Jones told his tale--how he wanted to carve out a niche and how he

loved music. It was the time when rock-and-roll musicians were riding high and

Jones wanted to shoot The Who and the Rolling Stones. "And," he

added, "I liked the good life of the times--you know--sex, love,

and rock-and-roll!"

|

|

|

One day he realized that in many cases he didn't know what the performers looked like. "I would see four people playing horns up there and I didn't know who I paid my money to come to see," he says. "I needed to photograph them, to give them a face." Jones followed them, setting up times, often backstage or at rehearsals, stalking them until they would finally say yes. It was the beginning of an archival series remembering jazz musicians of the era.

Did the art directors flip out over the pictures? "Not even a wiggle out of them," Jones says. Did the magazines grab the images for editorial? "I couldn't give them away!" So Jones began supporting himself photographing for textbooks, a lucrative market in Boston at the time. But he continued to try and make his mark in the world of jazz, finally realizing that annual reports put food on the table, not the wail of a trombone no matter how his camera could almost make us hear it.

It was a labor of love.

Entering the exhibition area we face a 30" square silver print of Donal Fox, seated by his piano, his white scarf elegantly placed on his shoulders. It is a quiet, introspective portrait.

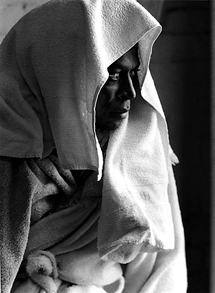

Then there's Milt Jackson, head in his hands, next to a rare image of Miles Davis, the great one swathed in towels after finishing his workout at a gym in Boston. Jones had found Davis at the gym; a fortunate fluke as someone had tipped him off that Davis was there getting in shape after his two years of semiretirement following an automobile accident.

- Log in or register to post comments