UP, DOWN, & SIDEWAYS

So let me start at my own beginning. I had an accident my first year in the military (Korea) and asked for a different job, as a photographer. I got it, but no training for it, and was assigned as the only photographer in a large unit, with an office, darkroom and a camera. I had no choice, I had to learn how to do the job on my own. I had been reading a lot about photography as there was little else to do where I was stationed if you didn’t drink or gamble, and I found both boring. And fortunately all of the instruction books that came with the equipment in my office and photo lab were neatly filed, so I had a guide. And I was there to do records of accidents, so for long periods I had nothing else to do but practice photography. My camera was a 4x5, so it was easy to make exposure brackets of all of my test shots, and to develop each sheet individually for different times. So trial and error taught me how to get the results I needed. It worked as I recently scanned some B&W film from my service days and they fit into an article I published in Shutterbug nicely.

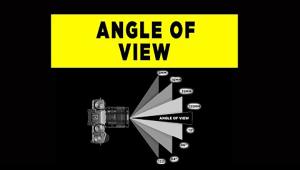

After 4 years of service and practicing how to photograph I was discharged and went home with the GI Bill to go to school to study photography and everything associated. My first year was as at a local university so I could spend some time with my mother. But then I came down to California and a photography school where I learned I would just continue to do what I had been up to, learning photography by doing it. But, now I had instructors and expert evaluations of what I was doing, plus new instruments to measure my results, a densitometer. Later on densitometry became popular as the Ansel Adams Zone System, but I never understood why the Zone System was popular and densitometry was thought to be so difficult. Anyway, my training confirmed what I had begun with. You obtain control of how to photograph by learning the process and how the tools like lenses, shutter/aperture, light meters and densitometers provide an understanding of how a subject is reproduced in an image on film and then paper.

You have to experiment with variations, and record what you did, and it will be the errors that will tell you what method to use. As I got to use all kinds of cameras, lenses and films as well as processes as a photo magazine staffer, I learned the tools that really make a difference are those that measure the subject and the film result. So I acquired the best densitometer I could get and also the best light meter, which at the time was the first Minolta 1 degree spot meter. I also learned from a great fine art photographer, Oliver Galliani, that a test reference step-tablet made with precise filters and illuminated from behind provided a longer range of values and more precise test results. So I experienced ever better control over what I was doing, and whether with camera X, Y, or Z, I could obtain pretty much the same predictable results. In other words, if you know the photographic process, know and have control of what the tools do, you have what is needed to get the images you make with just about any camera.

With film there were always unpredictable variables, like one emulsion batch differed from the next, each processing differed some from another because of replenishment and age of the chemistry. This is what I refer to as sideways variation. It can be limited by buying very large quantities of film and keeping the supply in cold storage until used. Processing variation can also be limited I found by using a chemical concentrate, diluting it for use, and then discarding it afterwards. With digital you have the advantage that sideways variation is almost eliminated. The ups and downs of exposure control to match it with subject variation is within what the camera records by varying the range that is recorded with internal camera controls. And all this can be further refined with software after the image is recorded in a file. Although the cameras and lenses look like those used with film, there is nothing comparable between a digital image, which is just pure information that can be changed easily and a film image which is locked into a prison of physical existence.