Alexander Gardner

History Made, History Recorded

Gardner had gotten the telegram from the War Department the day before at his Manhattan brownstone. It said that John Wilkes Booth, who had been at large for 12 days after killing Lincoln, had himself been shot and killed at Garrett's farm in Virginia. The Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, who was in charge of the Lincoln murder investigation, requested that Gardner proceed to the Navy Yard on the morrow to photograph the conspirators who were being held captive there.

The Conspiracy

Like most Americans, Gardner had read in the newspapers of the Confederate conspiracy

Booth inspired. His brilliant idea was to assassinate, in one night, the President,

Vice President, and Secretary of State, the upper echelon of the Executive Branch.

With no one to lead it, the Executive would fall and with it the Republic.

On April 14, 1865, at the evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's

Theater, Booth himself shot Lincoln. Then things began to really go wrong. Booth's

escape was interrupted momentarily by a broken ankle suffered upon a leap to

the stage.

George Atzerodt, who was supposed to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, could

not go through with it. Lewis Paine, meanwhile, broke into Secretary of State

William Seward's home and tried to cut his throat but failed. Seward had

had a carriage accident and wore a protective leather neck brace. Paine had

to settle for a panicked slice of Seward's face. Escaping into the night,

Paine was captured soon after, as were all the conspirators.

It was Stanton who had ordered the conspirators to wear canvas hoods that covered

their heads and faces. Besides Paine and Atzerodt, there was Davy Herold, Michael

O'Laughlen, Samuel Arnold, and Edman Spangler. They were held in shackles

aboard the ironclad vessels Montauk and Saugus. The ironclads were unwieldy

iron rafts meant only for coastline duty since they were too heavy to plow the

open seas.

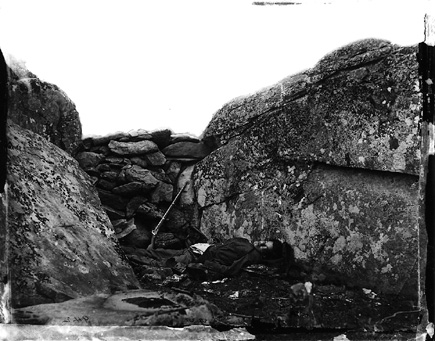

Deep in the bowels of the Montauk, Paine struggled with his shackles and his

thoughts. It was there, in that dark, dank hole that Gardner produced what some

consider his greatest work.

The

Photographer's Story

The

Photographer's Story

Alexander Gardner was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1821. By adulthood, he had

become a committed socialist. In 1850 at the age of 29, Gardner, his brother

James, and seven others of his group crossed the Atlantic. Arriving in New York,

they went west to Clayton County, Iowa, where they built a cooperative socialist

community. Gardner soon returned home to fund raise and recruit new members.

And then, as happens so many times in the lives of young artists, fate took

a hand.

In May, 1851, Gardner visited the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, a celebration

of contemporary technology where he saw the photographs of Mathew Brady. It

was a transformative moment. Soon afterward, Gardner, who had always been interested

in chemistry, began experimenting with photography. He also began reviewing

photographic exhibitions for the Glasgow Sentinel.

In the spring of 1856, Gardner came to America again, this time for good. With

him was his wife, two children, and his mother. Some of his family was tubercular,

requiring expensive medical treatment. Abandoning his socialist ideals for the

practical requirement of making a living, Gardner and family settled in New

York City, where he quickly got a job as a photographer with Brady. That's

where he made his initial reputation as a master printer of collodion.