Is It the Camera or the Photographer?: Sometimes It’s Both

One of the most enduring and ubiquitous axioms in photography is that it’s the photographer behind the camera, not the camera itself that creates the image. Or, as one guy commenting on my recent article "My 10 Favorite Film Cameras" trenchantly put it, “In the end, the equipment you use doesn’t mean squat.”

As with most aphorisms, there’s more than a grain of truth in these sentiments. Ansel Adams shot some awesome pictures with a Kodak Brownie box camera because he was a great photographer, and many memorable images have been created using modest equipment and mediocre lenses. And, as we have all had dinned into our ears ad nauseum, “Shooting with a great camera like a rangefinder Leica doesn’t automatically turn you into Henri Cartier-Bresson or Sebastiao Salgado,” both renowned Leica aficionados.

Perhaps the most widespread corollary to the statements above is that the camera is to the photographer as the paintbrush is to the artist or the chisel is to the sculptor – it’s just a tool, and it’s the final results that count. Well, it’s hard to argue with the second point, but I beg to disagree with the first.

Photography is a technologically based art form, and the camera used to make an image does have a significant impact on the final image, and not just from a technical point of view; it also affects the aesthetic elements, and even the emotional “feel” of the image.

And while you can’t state with certainty which camera or lens was used to capture a given image simply by looking at the picture, the equipment used plays an integral part of the creative process, and even the photographer’s shooting experience with different cameras and the techniques they use can have a profound effect on the final results.

WeeGee’s Speed Graphic

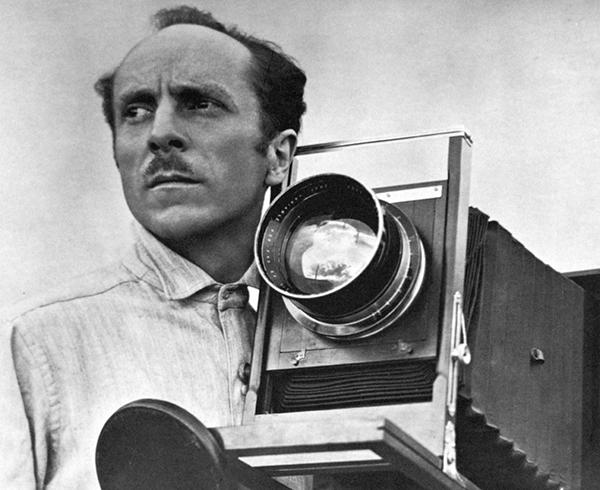

A great example of the influence of equipment and its concomitant techniques is the work of WeeGee (Arthur Fellig) a hard-bitten New York newspaper photographer and one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century, acclaimed for his raw, unflinching, and occasionally surreal and humorous images of the seamier sides of street life in New York from the ‘30s through the ‘50s.

WeeGee’s famously messy sedan was equipped with a police radio so he could be first on the scene of murders, fires, and assorted mayhem, which he recorded with a ponderous 4x5 Speed Graphic press camera. His brutal technique: Screw one giant Press 22 flashbulb into a BC flashgun fitted with a big shiny reflector, set the focus set at about 15 feet, set the aperture at f/16 or thereabouts, and blang!

In short, to minimize response time and get the shot to the paper as quickly as possible, WeeGee often used his Speed Graphic like a giant box camera. His timing was phenomenal, his instinct for telling a compelling story in a single image was legendary, and he had an incredible eye for composition, all of which made him a great photographer.

But in addition to his talent, it was the equipment he used, and the resulting techniques, that give his images their signature quality, expressing both his inimitable style and his pugnacious personality. Could he have shot them with, say, a Rolleiflex? It may have been more convenient, but the newspaper darkrooms of the day were set up to handle sheet film, and besides, they wouldn’t have looked the same. If you want to see some of WeeGee’s work, Google him or check out the images in his iconic book, "Naked City."

The Rolleiflex Experience

One of the things that rekindled my interest in this subject began last year when I dusted off my old 1950s Rolleiflex Automat MX and embarked on a project of shooting a series of what used to be called “character portraits” on black-and-white roll film (Kodak Tri-X and Ilford HP-5). I broke out my old Rolleinar #1 close-up lenses, which let me focus this fixed-lens twin-lens reflex down to about two feet to fill the frame with the subjects’ faces, and provides parallax correction to boot.

The result is a series of images that, at their best, reveal something distinctive and telling about the people pictured, and offers some insight into their mode of being and personalities. Since I’m something of a portrait fanatic I’ve shot hundreds of similar images on DSLRs and mirrorless cameras and even printed out some of them in black-and-white, but the pictures I shot on the Rollei look different, feel different, and convey a different complex of emotions.

Perhaps some of this is due to the medium of film vs. digital, but I believe a greater part of it is attributable to the camera—and not just the camera itself, but also the experience of shooting with the camera.

With a twin-lens reflex like the Rollei you approach the subject with a different mindset, and you’re forced to take a slower more deliberate approach, setting the aperture and shutter speed, taking meter readings, and composing each frame as though it’s “for the ages.”

Camera and Subject

When working with certain types of cameras (such as a Rolleiflex), you’re also more likely to interact with the subjects directly, asking them to turn the head, lift the chin, hold an expression, etc. Do this artfully and the result can be magical; do it intrusively or tactlessly and the results can be disastrous—stiff, artificial, and totally unconvincing.

Granted, there’s no reason you can’t approach photography from a “large format view camera” or a “medium format TLR” perspective when you’re shooting with your pocket-sized digital point-and-shoot, and it might be a fascinating learning experience to try it and see what you get.

However, in general, the shooting experience you have with the camera varies with different camera types, and this does affect the character of the images you create a lot more profoundly than the choice of brushes affects a painting. Yes, the camera is a tool all right, and it requires an insightful photographer behind it to create memorable images that stand the test of time.

But the camera is a very special tool that does a lot more than merely record what’s in front of it at a given moment in time. To give you a better idea of what makes the camera so special, herewith a short list of how the camera (and lens) you use affects the final image.

6 Ways the Camera You Use Affects the Image

1. Rangefinder cameras (all formats) have a separate optical viewfinder whereas DSLRs, mirrorless digital cameras, and even pocket-sized digital cameras show you what the lens sees, in an optical viewfinder or, in the EVF or on the LCD, as a live feed off the image sensor in real time. With a rangefinder camera you’re essentially placing a frame on what you see with your eyes, and with a DSLR or live view camera you’re looking at the world through the camera. In both cases, you may be composing the shot in the viewfinder, and selecting a significant rectangle but there’s a subtle existential difference in the approach. Perhaps that’s one reason rangefinder cameras have long been favored by street photographers and photojournalists.

2. Medium format and large format cameras (analog or digital) use longer focal length lenses to cover the format at any given angular coverage and that results in a different “look” to the images, especially those shot at wide apertures. The shallower effective depth of field you get at any aperture with medium- and large-format cameras makes them especially suitable for portraiture, landscapes, still life, and other kinds of photography where a shallower depth of field can yield engaging pictorial effects.

3. View cameras and some other large-format cameras are almost always used on a tripod, which offers greater control, allows the use of small apertures and slow shutter speeds, and has the potential of delivering greater image quality and perspective control. However, such cameras are less convenient and slower to operate and more limited in their ability to shoot action subjects, such as sports, wildlife, and rapid sequences. That’s why artists who took a deliberate approach to their work, such as Edward Weston and Ansel Adams created some of their finest images with tripod-mounted view cameras. It’s also why landscapes or architectural perspectives why with view cameras have a qualitatively distinct “feel.”

4. Cameras with lenses based on classical spherical designs can create images with beautiful bokeh and a different look than images shot with modern, multicoated, computer-designed lenses. Classic examples: The ancient 50mm f/2 Leitz Summar that delivers charmingly soft images wide open, especially at the edges and corners of the frame, and beautifully sharp but “rounded” low-contrast images at f/5.6 on down, the older 35mm f/2 Leitz Summicron, renowned for its beautiful bokeh, or the old Rapid Rectilinear lenses fitted to many old folding and view cameras that capture images with excellent detail but with a soft “plasticity” at f/16. You can’t easily describe these characteristics effectively in words, but you know them when you see them, and that’s why so many mirrorless camera shooters are fitting classic old lenses to their cameras to express their artistic vision.

5. Digital cameras with auto-exposure, autofocus, and high burst rates are the best choice for capturing random fast action that can’t be anticipated, and the ability to shoot a large number of pictures in rapid succession in virtually any lighting situation increases your odds of capturing the decisive moment. A good subject, thoughtful composition, and precise timing are still essential, but the chances are that most of the recent great action shots of kids and animals you’ve seen were shot with cameras having these features, and images of this kind are far less common among archival images of the past.

6. Film cameras do not let you assess the image immediately after capture—you have to wait until the film is developed. Digital cameras can display the captured image immediately, a tremendous advantage because you can usually take a better shot while the subject is still available. However, this cuts two ways because developing the habit of making each shot count rather than “chimping” the LCD may help to make you a better photographer in the long run. That’s why adopting a “film shooter” mindset when shooting digital can have a positive effect on the technical and esthetic quality of your digital images.

- Log in or register to post comments